When I was about seven years old, my mother and I were walking in the vicinity of McClure Street just off W. Market and observed a man on the opposite side of the street who appeared to be under the influence.

As the hapless high-stepping chap staggered along, one of his feet literally slapped the pavement as if he had no control over it; the truth was, he didn’t. I asked Mom what was wrong with him. While I cannot recall her explanation, I now suspect that he likely was a victim of a malady known as “Jake Leg,” a term describing someone affected by ingesting large quantities of Jamaica ginger, a product containing a high concentration of alcohol.

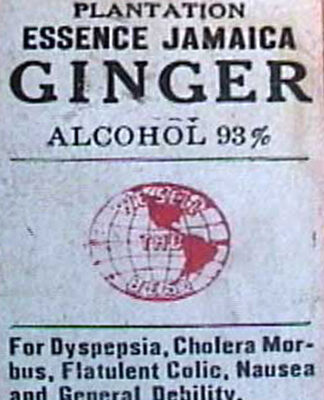

In early 1930, newspapers in the American South and Midwest began reporting an unidentified new paralytic illness that was affecting relatively large numbers of people. Oddly enough, the problem was not that prevalent in other areas of the country. The assignable cause was soon linked to Jamaica ginger, an advertised medicinal tonic legally marketed and sold as a remedy for a number of illnesses.

“Jake,” as it became known, had been in use from about the time of the Civil War. With the passing of the Volstead Act in 1919, the production of all commercial alcohol was forbidden in the United States with one notable exception – medicinal products.

Over the next several years, 50,000 to 100,000 people, mostly males, were permanently crippled with partial paralysis from the drink. The problem quickly crept into hobo jungles along railroad tracks of the affected routes. Compared to whiskey, Jake was much cheaper and had higher alcohol content. The product sold between 1920 and 1930 caused no significant health problems other than the usual alcohol related concerns.

The dilemma occurred when manufacturers decided to add an industrial plasticizer to the drink known as TOCP, which was mistakenly thought to be harmless. The tasteless, odorless and colorless additive was put in the drink to mask the high alcohol content detected during government tests of the product. Also, Jake was highly adulterated with molasses, glycerin, and castor oil to lessen the objectionable ginger taste, making it somewhat more palatable to consumers.

Jake leg caused neurological damage to the body particularly to the spinal cord. The first visible sign of it was a gradual paralysis that affected the lower extremities, thus giving it its name. As a rule, the condition was temporary but sometimes became permanent and even fatal.

The plight of these sufferers became the subject of numerous country songs with such titles as “Jake Leg Blues,” “Jake Bottle Blues,” “Jake Walk Blues,” “Jake Leg Wobble,” “Got The Jake Leg Too,” “Jake Leg Rag,” “Alcohol and Jake Blues,” “Jake Liquor Blues” and “Jake Walk Papa.” Artists of that era included Lemuel Turner, The Allen Brothers, The Ray Brothers, Byrd Moore, Narmour and Smith, Tommy Johnson, Ishman Bracey, The Mississippi Sheiks, Daddy Stovepipe and Mississippi Sarah, Asa Martin and Willie Lofton.

After the Food and Drug division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture took a serious aim at the problem, the popular drink became illegal, but many habitual users skirted the law and managed to locate supplies of it.

After about six years, Jake Leg became history. Today, only the scratchy echoes of the old songs taken from worn out 78-rpm records remind us of the affliction of yesteryear: “You're a Jake walkin' papa with the Jake walk blues; I'm a red hot mama that you can't afford to lose.”