Monday, March 6, 1961 was a much-anticipated day for Science Hill High School students. On that date, the majestic old downtown high school building that was razed and rebuilt in 1910 on what students referred to as “The Hill,” ceased to be the city’s main high school.

Workmen take a break while building the “Old” Downtown Science Hill High School in 1910

A great deal attention was drawn a few miles to the north where the baton of progress passed forward to a new long-awaited modern, expansive facility. Linda Moore Hodge, who graduated in the first class from the new facility, saved and shared the opening day Johnson City Press Chronicle with this writer. Local advertisers flooded the paper with congratulatory remarks.

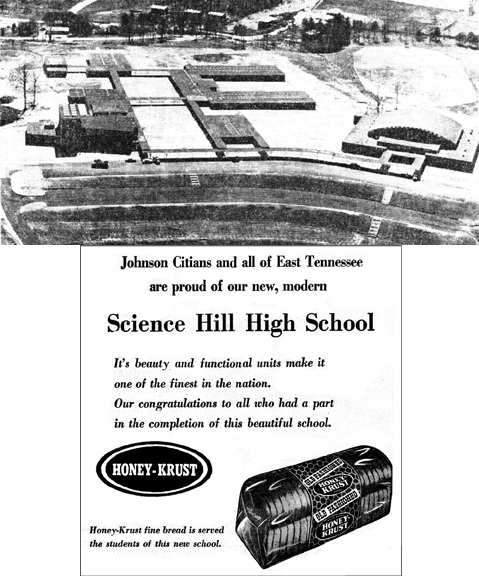

The “new” Science Hill High School as it appeared just prior to occupancy in 1961. Many businesses congratulated city officials for the accomplishment.

The new innovative $2.5 million campus-style school was a dream come true, brought about by a growing student population and a cramped aged facility situated in the congested business district. The new structure did not materialize overnight; serious discussions for it originated in 1957. During November of that year, Johnson Citians went to the polls and voted to issue $2.6 million worth of bonds, which were offered to the public the following March.

Thus began a flurry of activity. Board members and city officials visited selected campuses in several southern cities to formulate ideas for the new Science Hill. It became readily apparent that multiple campus-style buildings offered the most economical option that would satisfy existing and future needs.

A 40-acre site was selected at the intersection of John Exum Parkway and N. Roan Street. A sizable quantity of land was needed, far in excess of the 2.5 acres that the downtown school occupied. The acreage was sufficient to provide for six separate interconnected buildings with covered walkways, a gymnasium, ample parking space and plenty of outside practice fields for athletics.

Although official groundbreaking began in December 1958, actual construction did not start until the following July. Even then, a steel shortage halted work for a period of time. Further, a large hill that originally occupied the new site had to be leveled. In an almost unanimous decision, school officials retained the same name as the old one. Leland Cardwell was selected as the architect and J.E. Green and Company was awarded the construction contract.

Science Hill was declared to be the largest electrically heated school in the world. Most rooms had hookups for future air-conditioning needs. In all, the sprawling complex occupied 104,500 square feet of floor space.

The auditorium/theater complex sported an impressive foyer with terrazzo floors and colorful tile walls. A steeply inclined floor made it easy for 800 seat occupiers to see the stage. There was space overhead for 25 sets of lights plus a required fireproof curtain. Skylights over the stage could be darkened by simply regulating shades that covered each section. In front of the stage was room for a good-sized orchestra.

The acoustical ceiling band room had ample storage space for instruments, a recording room and sheet music space. A soundproof choral room was designed to handle large and small groups of singers.

The nerve center of the new campus was the Administration Building, which was centrally located among the other buildings. It contained a 2-way public address system connected to all rooms along with closed circuit telephones (internal house phones limited to the campus with no incoming or outgoing call capability), a public address system and a radio hookup. An emergency bright red “hot phone” was available that allowed the caller who picked up the receiver to be automatically connected with every speaker in the school.

The Classroom Building contained 24 rooms that were described as being “light, bright, spacious and attractive, and it may be some time before the first students can stop admiring it long enough to concentrate on studies.” In it were the science laboratories consisting of a combined chemistry and physics laboratory, one dedicated chemistry lab and a third one for biology. A special projects room allowed students working on long-range projects to leave them set up for days or weeks.

The library had two separate reading rooms, with each surrounded by easy-to-reach books on head-level shelves. The rooms were separated by the librarian’s office, the check out counter and a conference room that allowed groups of students to work on common projects. The library lobby was furnished informally, thereby inviting students to relax at free times and enjoy literary gems. A feature not usually found in other schools was a night depository, permitting students to return books after hours.

The Useful Arts Building contained the home economics department, which consisted of two rooms with three complete kitchen units, stoves, refrigerators, storage space and counter workspace. In these two rooms were sewing machines, cutting tables and fitting rooms. Here young ladies learned to sew a fine seam on sewing machines of all types, be it making pajamas or an evening gown. Another section of the building contained the well-lighted art department.

Entering the gymnasium, one encountered a foyer that was large enough to serve as the ROTC drill hall during the day and accommodate 2,500 basketball fans at night. A floor-to-ceiling partition could be activated to quietly and quickly expand across the entire length of the gym, separating two full size basketball courts. Another button allowed 2,000 rollaway seats to come out from the sides. Using folding chairs on each end of the gym provided accommodations for an additional 500 people.

The cafeteria’s main dining room seated 350 students utilizing four food lines with two designated for students desiring a hot lunch and two for those wanting a cold snack. The lobby contained informal furniture where students who had caught up with their studies could go for relaxation. The dining hall could be cleared of tables and chairs for school socials. Also, a terrace with southern exposure allowed students to bring along their charcoal burners and have a cookout for class, school or special group events. The kitchen was 100% stainless steel throughout ranging from a walk-in refrigerator to a shining commercial type dishwasher.

The new Science Hill High School was dedicated and opened to the public on Sunday, March 5 at 2:30 p.m. in the gymnasium. The Education Committee of the Chamber of Commerce handled arrangements for the important event. On hand were current board members: R.T. Haemsch (chairman), William Sells (vice chairman), Forrest Morris, George Speed, Dr. E.T. Brading, Viola Mathes and Mrs. N.T. Sizemore. Former board members who had a hand in the project were Gerald Goode, L. Cecil Gray, John Howren and Ray Humphreys.

City Manager David Burkhalter presided over the ceremonies: The school band played the National Anthem. Rev. Ferguson Wood, pastor of First Presbyterian Church, gave the invocation. Mr. Burkhalter introduced special guests. Mayor Ross Spears made the building presentation, which was accepted by R.T. Haemsch, chairman of the Johnson City Board of Education. Thomas Boles directed the high school choir, after which Frances Harman, a senior, sang the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Howard McCorkle, superintendent of city schools, then introduced Dr. Andrew Holt, president of the University of Tennessee, who gave the keynote address. Rev. James Canady, pastor of Central Baptist Church, offered a prayer of dedication and benediction. The dedication service was concluded after Mayor Spears and the audience provided the litany for the dedication.