In the 1950s, many of us can recall owning a phonograph with a selection lever near the turntable that allowed the listener to chose between four separate record speeds: 78, 45, 33.3 and 16 rpm (approximate numbers).

As a child in the late 1940s, I became a devotee of 10-inch 78-rpm records after my Grandmother Cox gave me her collection of discs that she stored in a sturdy fabric case with a hinged lid. Cardboard dividers inside the case separated and identified the selections. During this time, I was recovering from a bout of rheumatic fever that greatly restricted my physical activity, including walking, for six months. I spent hours sitting in a chair while being entertained by my close proximity combination radio and record player console.

I handled my fragile collection carefully and kept them inside the case when not in use. Records came in paper sleeves with circular cutaways that allowed the labels on both sides to be visible. Each side of the disc was limited to about three minutes of playing time.

By the 1950s, I had graduated to 7-inch 45-rpm records, even though 78s had by then become unbreakable. The 45s attracted the younger crowd with its trendy compactness and unique large hole in the middle. Newer phonograph models had to be redesigned to play them. Otherwise, the user had to put an insert in the larger hole or place a small round disc about the size of the hole on the turntable.

For a period of time, manufacturers released selected hit songs at both 78 and 45-rpm speeds while consumers began making the transition to the newer format. The 78s were rapidly heading toward extinction.

Next came 12-inch 33.3 records, known as “long play” records that typically contained six songs per side for a total of about 30 minutes of music. This new multi-selection format quickly became popular with record aficionados.

The fourth speed on the selector lever was for 16-rpm records, which arrived in 1953. I never owned any records with this speed. Why then was this speed put on record players? Truthfully, some manufacturers omitted the 16-rpm speed option on their machines. Although I cannot recall ever seeing a record of this speed in racks at the Music Mart, Smythe Electric or other downtown record shop, I suspect the businesses had some behind the counters for sale to customers who requested them.

The16-rpm records had a distinct market. The plus for the slower speed was much longer playing time; the minus was decreased sound quality, but the products did not necessitate this. Also, they were generally pressed as monaural (one-track) instead of stereo (two-track). They were ideal for low volume “dinner” (a.k.a. “elevator” and “filler”) music because one side would play for an entire meal without anyone having to change it. If a family held a Christmas outing at their home, they could play 16-rpm records of holiday favorites that would set the tone for the evening with infrequent attention to the machine.

The records also offered an advantage to the blind who were able to listen to them for long periods of time without having to change sides or disks.

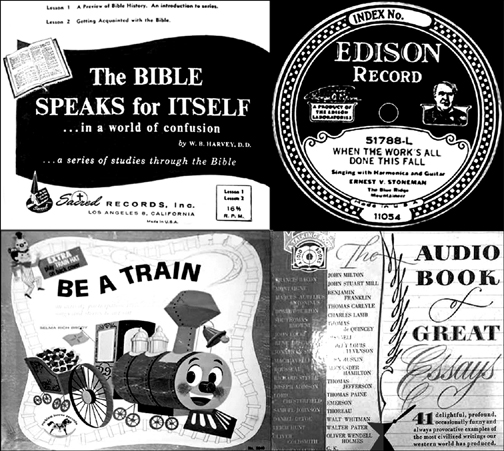

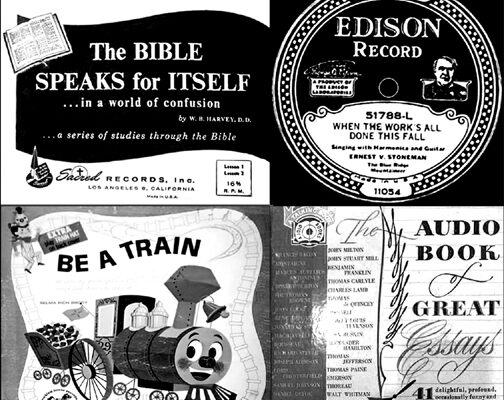

My column photo shows four additional uses of 16-rpm records (left to right, top to bottom): sets containing the “Spoken Bible”; Edison recording of Ernest “Pop” Stoneman, known as the Blue Ridge Mountaineer, singing hillbilly ballads; children’s records such as “Be a Train”; and “The Audio Book of Great Essays.” Older folks may recall when 16-rpm records were used to distribute political campaign speeches. Also schools incorporated them in classrooms to teach foreign languages.

As the parade of progress marched along, next came reel-to-reel, 8-track and cassette tapes, but that is the subject of another column.

Comments are closed.