In early 1933, Johnny Roventini, who stood 47 inches tall and weighed a mere 59 pounds, was touted by the New Yorker Hotel, where he worked, as the smallest bellboy in the world. One night, he became acquainted with two advertising agents for the Philip Morris Company, who had conjured up a publicity stunt for a cigarette commercial. They offered Johnny a dollar if he would locate a Mr. Philip Morris in the hotel. In actuality, there was no one there by that name.

Roventini strode through the hotel shouting, “Call for Philip Mor-raaas.'' He exaggerated the second syllable using an exaggerated, drawn out “raaas” instead of a quick “ris.” “I just went around the lobby yelling my head off,” said Johnny, “but I disappointedly couldn't get Philip Morris to answer my call.”

Johnny soon received a lucrative offer from the company, but he was hesitant about accepting it. After all, he had a decent financial contract with the hotel, drawing a salary of $15 a week, plus an additional $10 in tips. He decided to think it over and reportedly told them, “I'll have to ask my mother.” After delaying his decision for several months, Johnny resigned his hotel employment on September 16, 1933 and signed a lifetime contract with the Philip Morris Company.

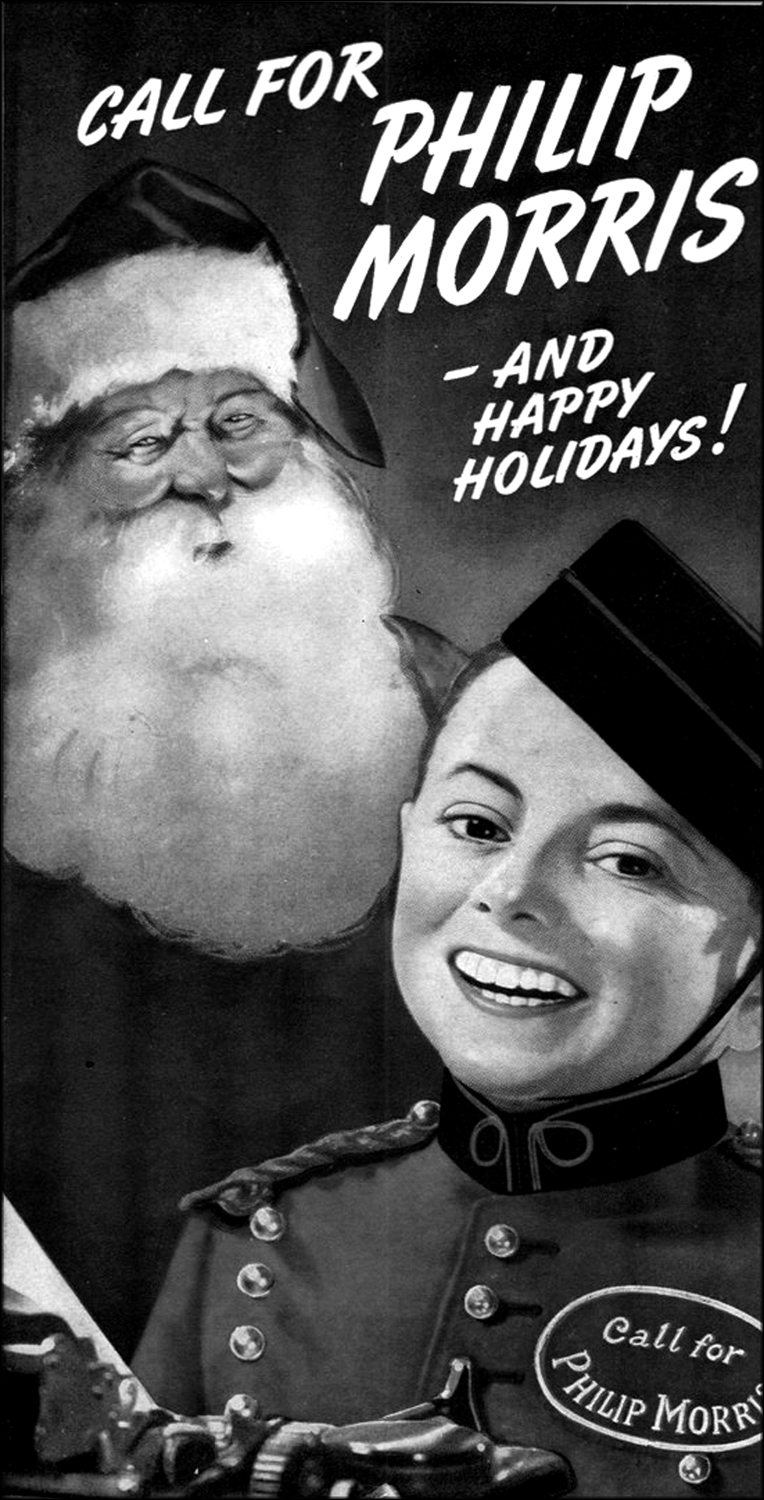

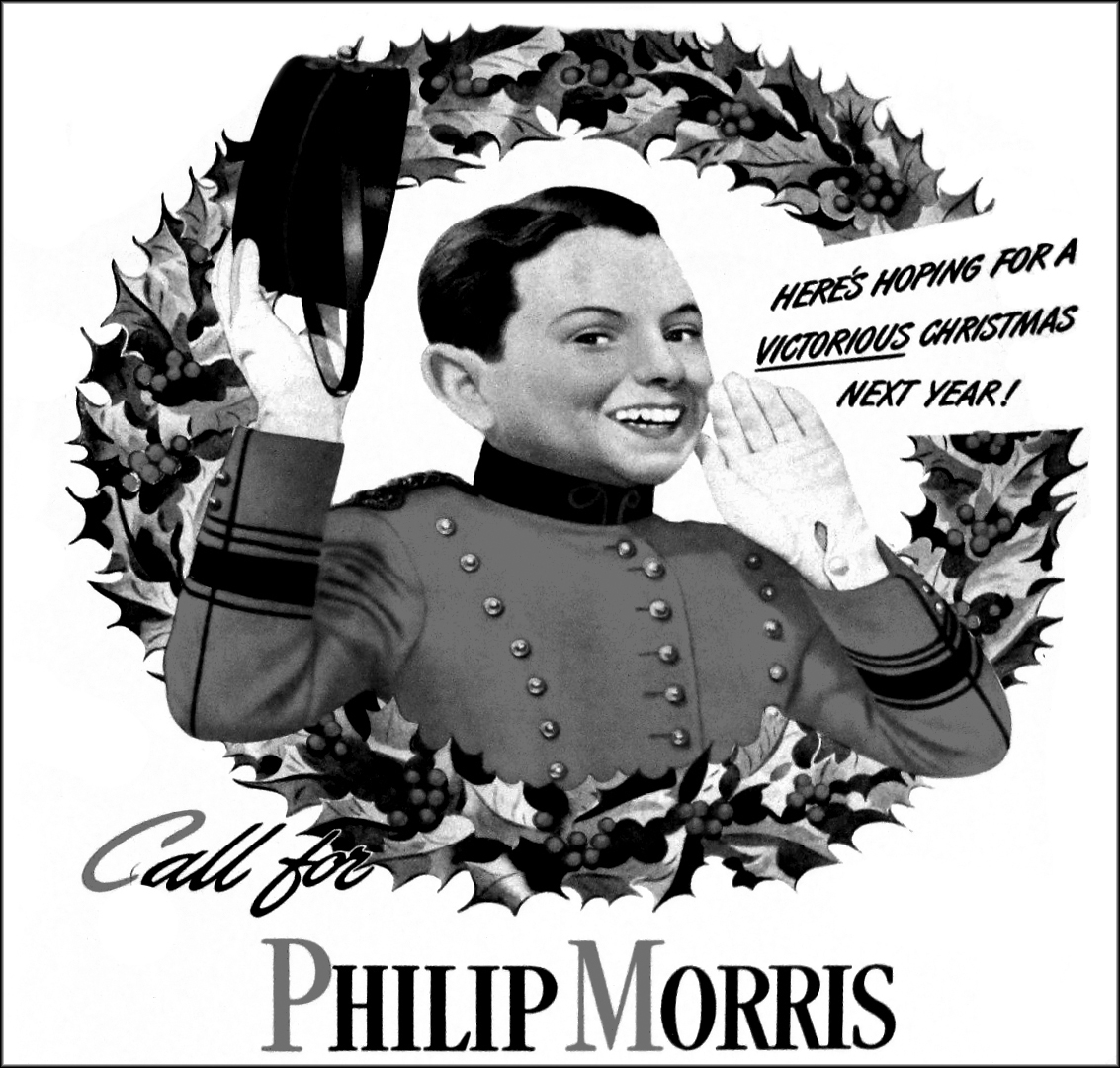

Thus began a career that landed Roventini a lifetime contract and an annual salary of up to $50,000. Johnny, who always appeared in his short-jacketed bellboy outfit, became Philip Morris Company's “living trademark.'' The little guy once estimated that, over the years, he called out the cigarette slogan more than a million times and shook hands with about the same number of people.

Johnny was first heard on the air on “The Ferde Grofe Show,” who was a composer, arranger and pianist. Stardom came to him almost overnight and sales success of the Philip Morris brand followed suit as both skyrocketed to fame. Johnny saw the company grow from a single product manufacturer to a multi-brand, highly diversified corporation.

To protect Johnny and the Philip Morris Company, the company's contract forbid him from appearing in public without a bodyguard; riding the subway during rush hours was also forbidden. And for fear of kidnappers, his home address was kept undisclosed. The company was taking no chances. Johnny was indeed a top salesman and a most valuable property. His Cinderella rise to fame led him to appear on Philip Morris radio programs with outstanding orchestras.

The little fellow began playing key roles in many great radio productions: Horace Heidt's “Youth Opportunity Hour,” “It Pays To Be Ignorant,” “Ladies Be Seated,” Johnny Olson's Luncheon Club,” Walter Kiernan's popular “One Man's Opinion,” “Crime Photographer,” “Music You'll Remember,” “The Kate Smith Show,” Johnny Mercer's “Call for Music,” “Break the Bank,” Ralph Edward's “This is Your Life,” “The Mel Torme Show,” “The Rudy Vallee Show,” “Candid Microphone” (forerunner of television's “Candid Camera”) and others.

Every Philip Morris show featuring Johnny became just as famous for its closing line as for its opening: “This is Johnny again, returning now to the thousands of store windows and counters all over America. Look for me. I'll be waiting for you. Come in and, of course, “Call for Phil-ip Mor-rees.”

At the height of his radio career, Johnny was in high demand for major public events such as fairs, conventions, trade shows, club meetings, festivals, military parades and the like. He found it impossible to attend everything, so it was during that period that four look-alike assistants, known as “Johnny Juniors,” were employed to represent him at some of the functions.

No matter where he appeared, he was invariably asked to give his famous call, which he did. To please his worldwide audiences, Johnny learned to deliver the words in French, German, Spanish, Swedish, Italian and Chinese.

People crowded to see him; it was said that when they saw him, their heart began beating a little faster. It wasn't his size or the lack of it, but rather the fact that he made people feel what he was made of – goodness and greatness, as well as the warmth and gentleness that was the little man himself. He was created as a trademark for the Philip Morris Company but became an American legend. For 25 years, he walked among his fans and they became richer for it.

In later years, when Johnny was asked to name some of the memorable ladies with whom he worked, he responded with Barbara Stanwyck, Tallulah Bankhead, Rosalind Russell, Deborah Kerr, Paulette Goddard, Constance Bennett, Dorothy Lamour, and the two incomparable great stars, Madeleine Carroll and Marlene Dietrich?”

After the war, the radio shows began to bow to television, and for a time Johnny introduced early Philip Morris video shows such as “My Little Margie” (Gale Storm), “Tex and Jinx; (Tex McCrary and Jinx Falkenburg), “Candid Camera” (Allen Funt), “I Love Lucy'” (Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz), “The Red Skelton Show,” “The Jackie Gleason Show,” “Hazel,” “Hogan's Heroes,” “Thursday Night at the Movies,” “Slattery's People,” “The Loner” and even “The CBS News with Walter Cronkite.”

According to Johnny, “Lucy was my real love; our friendship has been a lasting one and the memories of our having worked together are among my fondest. She not only was a great comedienne but a great lady as well.” Johnny transitioned effectively from the role of a radio and television performer to that of a roving ambassador of good will man for Philip Morris.

When Johnny Roventini died on Dec. 3, 1998, the New York Times commented in his obituary notice: “Johnny's fame as an advertising legend was enhanced by an ever-present smile and outstretched hand that won him friends wherever he went.” On that sad day, the highly recognized “Call for Philip Mor-raaas” went silent forever. In all those years, he never found Mr. Morris, but he found something else – a world of people who greatly loved and adored him.

Comments are closed.