“Go west, young man (and grow up with the country)” became a rallying cry in the United States in 1865, popularized by American author, Horace Greeley. It concerned Manifest Destiny, massive expansion across the continent.

The newspaper editor advocated westward growth because he believed the fertile farmland that extended throughout the west was an ideal place for hard-working people to succeed. Young men from Virginia, Tennessee and the Carolinas readily heeded the call.

Promotions by western railroad agents that beguiled young men with exaggerated tales of high wages and plentiful opportunities in the west. With imaginations inflamed by these fanciful “artful dodgers,” they saved their hard-earned cash for the extensive and expensive journey ahead. They arrived to find that the west was saturated with hopefuls like themselves who were looking for easy money that did not exist. They likely could have done as well or perhaps better had they stayed home.

Some found higher wages, but with them came increased living expenses. Instead of land being cheaper, it was often higher and fraught with added costs, including irrigation equipment needed to make the ground more fertile. Even when productive crops were grown, the railroads took the bulk of the profits in transporting them to populated areas where there were enough residents to consume them.

Many young men drifted from place to place, which further added to the railroad’s revenue. Countless drifters, realizing their circumstances were not what they desired, longed to return home but were too embarrassed to do so. They learned that there was no pot of shiny gold waiting for them at the end of the rainbow because the land was too desiccated to produce the colorful arc. Indeed, the “fine medicine” that was advertised in local papers was not for the drifter from the east but for the greedy agents who solicited them.

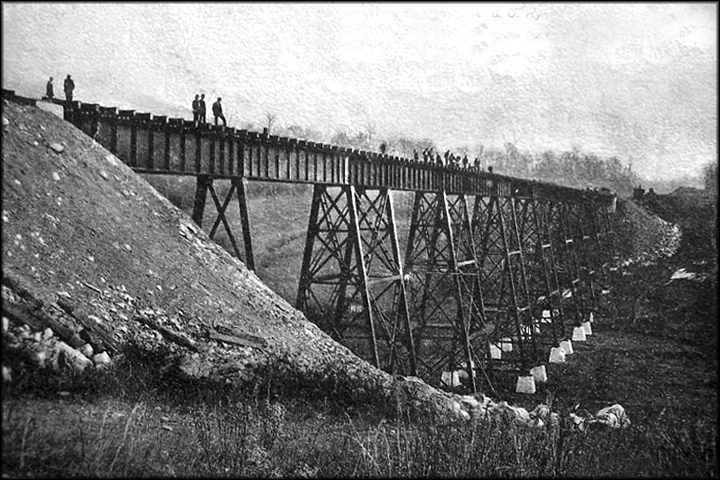

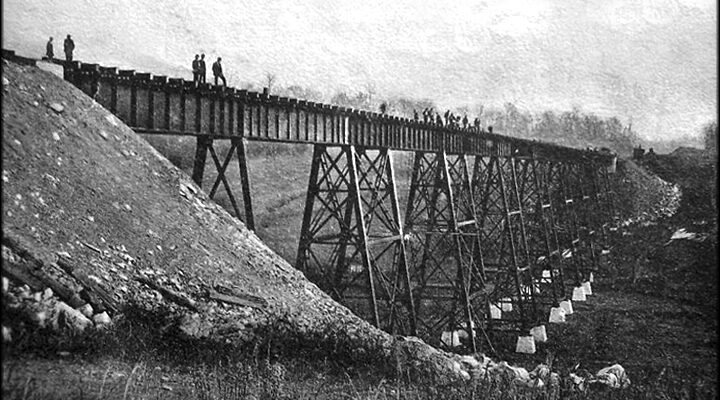

CC&O Railroad Trussle in Boones Creek

My September 5, 2011 Yesteryear column dealt with the festive celebrations that occurred in Johnson City and Spartanburg with the completion of the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railroad between Dante, Virginia and Spartanburg, South Carolina on October 29, 1909. The new railroad, built at an enormous cost brought by significant engineering challenges from laying track over abnormally rough terrain, was now ready to transport coal from a rich coalfield in the mountains. The risky venture greatly enhanced the economic outlook of the area.

By 1910, mountainous folks initiated their own rallying cry to “Come back east, young man (and help move coal). Many of the native-born people had been gone for a considerable number of years. They were needed to lend a hand with the development of the country that had been opened up by the presence of the new railroad.

The economy in the four states was so greatly improved that it was advertised as “the most popular movement of recent times.” Local newspapers became the primary medium for convincing home folks to return to their native land.

The CC&O Railway printed 5,000 circulars for school children to use in gathering the names and addresses of persons who had moved west. In turn, they were delivered to the board of trade and then to the railroads participating in the “Back Home” movement. Also, the railroad placed identical ads in newspapers. It was estimated that a million former southerners were asked to visit their old homes.

Organizers underestimated how successful the “come back home” crusade would be to area residents. The campaign achieved its noble goal.

Comments are closed.