The mere mention of Henry Johnson evokes an image of Johnson City’s modest founder who among other duties served as farmer; storeowner; postmaster; hotel landlord; first mayor; and railroad depot, freight, ticket and express agents.

Johnson’s strong fervor and high energy level was instrumental in his developing the little mid-1800s mountainous village known as Johnson’s Depot into the sprawling prosperous city we know today.

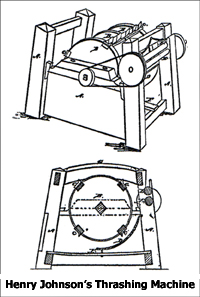

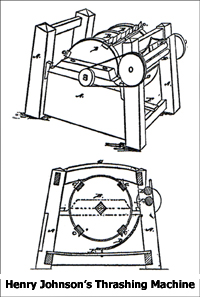

The founder had another contribution not generally known; he invented, developed, patented, manufactured and sold a threshing machine, a device used to separate grain from stalks and husks. This little-known fact surfaced in 1941 after Judge Samuel Cole Williams (donor of cash and land to Mayne Williams Library) spotted an advertisement in the October 1836 edition of “Tennessee Farmer” magazine. Johnson would have been 25 years old at the time.

According to the ad: “Johnson’s Thrashing (old spelling) Machine. We certify that we have seen in operation, by two horsepower, this machine which, thrashing at the rate of 48 dozen of wheat per hour, which is effectually cleaned. (Signed) John G. Ruble, Archibald Williams, William G. Looney, Jesse B. Hunter, George W. Hoss, Henry Massengill, John Hoss, Michael Massengill.

“Rights for Sale: The thrasher may be seen in operation at the plantations of Mrs. Sarah Hammer and William Massengill in Washington County. Apply at John Hoss on Brush Creek or at the subscriber in the neighborhood of said Hoss. (Signed) Henry Johnson, September 6, 1836.”

The name, John Hoss, is significant because Henry married John Hoss’s daughter, Mary Ann. Williams contacted the Patent Office in Washington DC and received confirmation that the invention was patented in the name of “Henry Johnson of Washington County, Tennessee” on May 29, 1835. The judge, in turn, documented his discovery in an article for the May 4, 1941 edition of the Johnson City Staff-News.

The new innovation was an important contrivance in the first half of the 1800s and afterwards since wheat was the leading money crop of Tennessee. Washington County was considered premier among the other counties in the state for wheat production harvesting grain that was highly sought after because of its hardness and milling quality.

For this reason, flourmills were abundant throughout the countryside. Several businessmen of Jonesborough and local millers formed small businesses that shipped flour down the Watauga, Holston and Tennessee rivers to markets as far south as the northern regions of Alabama and Mississippi.

Among the participants in this endeavor were two leading Jonesborough mercantile firms, Crouch and Emmerson (W. Crouch and Thomas B. Emmerson) and Carter and Jones (David W. Carter and James H. Jones).

Emmerson was the son of Judge Thomas Emmerson who served on the Tennessee Supreme Court. When he retired from the bench, he moved from Knoxville to Jonesborough where he had been the first mayor and engaged in the practice of law and newspaper publishing.

In 1835-36, the elder Emmerson established the “Tennessee Farmer,” which he believed to be the first purely agricultural journal of the Central South. If true, Jonesborough has two noteworthy distinctions: the first agricultural journal and an 1820s magazine, “The Emancipator,” produced by Elihu Embree that was devoted solely to the emancipation of slaves.

Henry Johnson’s contribution to the thriving milling business was to invent, patent, manufacture, and sell threshing machines. Although it is not known how successful he was, his laudable venture was likely not overly successful because affordable and adequate transportation for moving manufactured products such as his new machine was difficult to find. This was prior to the coming of the railroads, thereby restricting access to markets due to the seclusion of East Tennessee at the time.

The majority of shipping vessels hauled flour and numerous articles fabricated of iron. Very little wheat was grown below Knoxville and almost none in Alabama and Mississippi, which were cotton regions. Another problem for Johnson was that his threshing machine was not the only product on the market; he received ample competition from Pennsylvania and the Valley of Virginia.

The magazine ad revealed those who were among the progressive farmers of the 1830’s in Washington, Carter, and lower Sullivan Counties. The George Hoss home was a log structure, which later gave place to a house of “more distinction.” John Hoss’s farm was located on what became known as Carnegie Addition, his residence having stood on the site of “Orchard Place” at what is now the land surrounding 825 E. Fairview Avenue.

John was likely the first Hoss in the area. His father, Jacob, developed the “Hoss apple,” a species believed to be destined to win a reputation of excellence throughout the land. Unfortunately, it was “improved” out of existence.

Another supposition is that the first manufacturing plant within the city limits was on the Hoss estate and operated by Henry Johnson.

The discovery of Henry Johnson as an inventor adds yet another accolade to this impressive man.