The first settlers in East Tennessee took up residence near the Watauga River where they had to adjust to the complications of life in the harsh mountainous region. Before leaving their homes in the East, these robust pioneers saved money for the trip by boldly selling their land and other possessions. Initially, many of them settled in the Appalachian Mountains, but eventually crossed the Mississippi River and headed farther west.

The families packed all the essentials they could reasonably carry on their horse-drawn wagons, including axes, rifles, cooking vessels, food and clothing. The lack of roads presented them with formidable challenges as they migrated across rugged terrain.

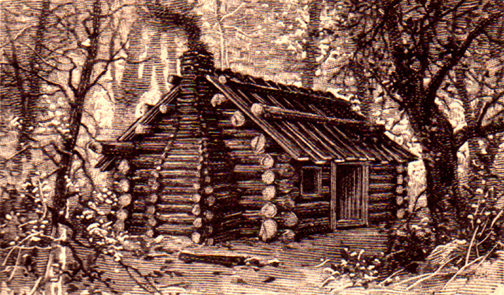

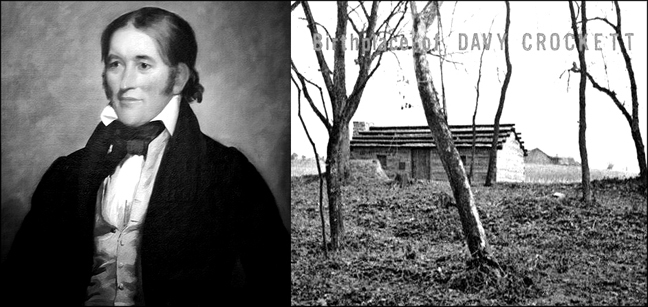

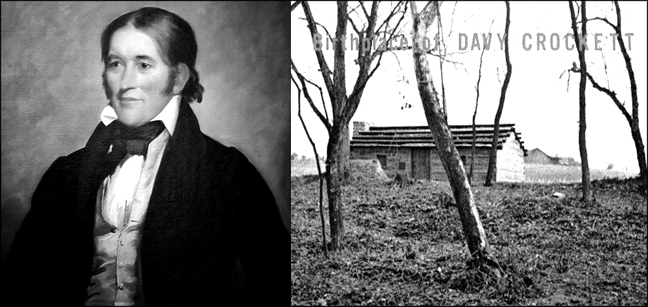

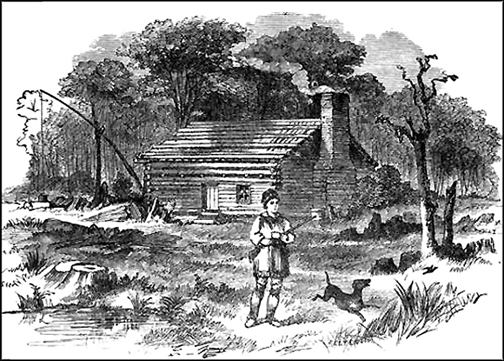

Their first order of business when they arrived at their newfound land was to build a rudimentary permanent cabin adjacent to a nearby spring of pure water. This meant finding temporary living quarters such as their wagons, beds of leaves under large trees, canvas covered lean-tos, one-room shanties and even teepees.

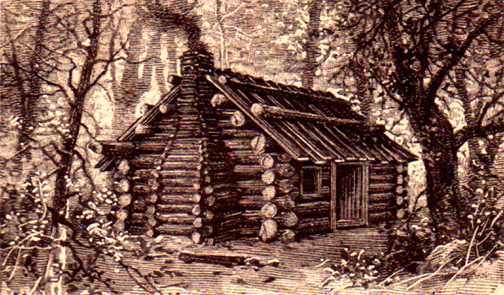

Every male old enough to swing an axe chopped down trees and other obstructions to afford them an opening in the thick forest for their new abode. They cut and fit tree logs together, sometimes “scalping” the wood (hewing or shaping it with numerous hard blows from an ax). This was tedious work because of the heaviness and quantity of logs required. They stuffed a mixture of mud and grass in the spaces between the logs to keep the elements and the varmints out.

The family had two options for a floor; they could leave the hard earth bare or cover it with heavy split slabs of roughly dressed timber known as puncheons. The roof consisted of clapboards held in place by straight wooden logs. A rudimentary door was cut in the south side of the house and a small elevated window was provided along the north side.

For many years, household furniture was crude but also functional. The cabin contained no fine furnishings such as bureaus or sofas. Instead, a bed consisted of nothing more than two poles pushed into cracks in a wall with the opposite ends resting on two rough forks cut from tree branches. On these were laid flat boards, which supported a bed tick (mattress) filled with leaves, straw or feathers from wild pigeons, geese or ducks.

Clothes were hung on wooden pegs in the walls around the room. The finest piece of furniture was generally a rustic chest that was used to store the family’s finest clothes and treasures.

Since bricks were not available then, chimneys were lined with rough, flat stones and soft clay. The fireplaces, which were used for heating and cooking, were usually outsized enough to hold half of a wagonload of wood.

A good water supply was essential for drinking, cooking, cleaning and bathing purposes, as well as storing and preserving butter, milk, fresh meats and other perishable items.

Initially, pioneer children did not attend school for two reasons – they were usually unavailable and youngsters, regardless of their ages, were needed for essential chores at home. Men and older boys hunted wild game. The meat was then cleaned, cut it into pieces and stored in salt, which preserved it until it could be eaten. Just prior to cooking, it was scrubbed to remove the salt. Another option was to store meat in snow barrels in winter.

Those were the days when adversity and strife often existed between settlers and Indians, thus forcing them to occasionally gather their belongings and seek refuge in forts or stockades. These hardy brave settlers eagerly sought a new and exciting way of life, which they received and more, usually exceeding their wildest expectations.