Bobby Harrell delights in discussing his four years of after-school work experience at the John Sevier Hotel that began in 1949 when he was 13. His father, Iss and uncles, Henry Street and Earl Harrell also worked there. Street was maintenance supervisor.

“I worked weekdays from 4-9 p.m., said Bobby, “operating the hotel’s freight elevator at the northwest loading dock. Sometimes I worked on weekends in the housekeeping department cleaning windows and wallpaper, flipping mattresses and performing other assorted jobs. My family lived on W. Walnut Street. I rode a city bus to the downtown station and walked along the train depot to the hotel. At night, I caught the bus back home. It cost ten cents to ride. In its heyday, the hotel stayed full, especially being so close to the train depot. I got frequent calls for service from maintenance workers, waiters delivering food to people’s rooms and others.”

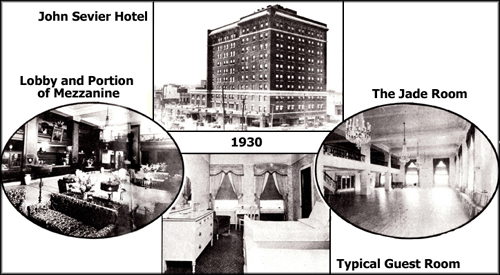

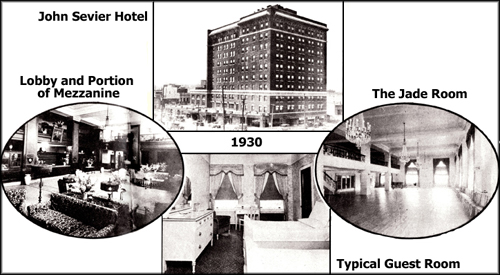

The rooms at the John Sevier had private bathrooms and steam heat in every room via radiators. Although there was no central air conditioning system, guests could request that a window unit be installed in their room for an added fee. Iss assisted Henry in all maintenance of the hotel and worked in the boiler room in the basement in cold weather months keeping the stoker going to supply heat to the building. Bobby recalled that the cellar had an old fashioned telephone with a receiver attached with a cord.

The basement was smaller than the upper floors, being located primarily under the kitchen and dining room. Since the hotel was built over five springs, pumps had to run continually to prevent flooding. One area was used for processing live chickens. A man, known as “Pop” Conley, performed this work at a large stainless steel workplace. The dressed birds were then placed in several large walk-in coolers. Meat arrived by the half and quarter sections. Transfers were routinely made from the basement coolers to one upstairs in the kitchen. The chef, whose first name was Norman, served as meat cutter.

“Another area downstairs,” said Bobby, “was where they made ice cubes. They filled metal cylinders with water and placed them in brine water. After the ice froze, workers used a large power table saw to cut large sheets of ice several times producing slightly larger than normal ice cubes. “The ballroom and dining room were very popular and in continuous use. The kitchen had a large stainless steel dishwasher. The large ballroom had a number of chandeliers, massive curtains and hardwood floors.

“Sometimes on Sundays, I worked as busboy, assisting waiters by carrying large trays of food to people’s table. The daily restaurant menu was printed each day at the first floor northwest desk. The typesetter inserted letters by hand into the machine and manually cranked out paper copies. It looked like a miniature version of an old printing press. After the chef prepared the menu for the next day, a man came to the food storage area in the basement with a four-wheeled buggy and returned with enough food for use in the kitchen the next day.”

Bobby remembered the hotel supervisor: “Monroe McArthur was the big boss when I worked there; we called him Mr. Mac. K.D. Hurley was assistant manager. Mac was a good fellow. He walked around all day singing the same little song, ‘Day Dee Day, Day Dee Day, Day Dee Day.’ Mr. Mac owned two automobiles, a 1950 Cadillac and an older Lincoln. He kept both parked on the Market Street (south) side of the hotel in reserved spots. Obie Belton was his personal chauffer and usually drove for him. Occasionally, Mac drove the car himself. Those were the days when automobiles had straight shift and a clutch. He would push the gas pedal to the floorboard and the clutch just about to the floorboard and ease out of the parking space with the motor flying and the car barely moving.”

Bobby recalls taking an inebriated painter on the elevator to the 8thfloor to paint some windows using a portable outside scaffold. He reported the man’s impaired condition to his uncle who, in turn, hastily went to the room where he was working. Henry found the worker with a window open and ready to attach his scaffold to the window. He was promptly escorted downstairs in spite of his insistence that he was not intoxicated. Outside scaffolds were attached to the inside of the windows, providing abstemious painters a safe way to access the outside of windows. Washing windows was done inside the room without the need of a scaffold. Since there were 250 windows in the building, cleaning was a never-ending chore.

A small laundry, located on the 10thfloor, handled the restaurant’s washing needs, but towels, washcloths and bed linen from rooms were picked up and washed by Johnson City Steam Laundry at 200 S. Boone.

Unlike today, where businesses have installers come in and replace large sections of carpet, one man replaced it in rooms and other areas almost on a constant basis. Salesmen, referred to as “sample men,” often came to the hotel with large quantities of clothes for public display. Bobby took them on the freight elevator to the display room. Bobby recalled when a man climbed the hotel from the Roan Street (east) side of the building in the late 1940s by carefully and methodically walking on and holding onto bricks. Such stunts were popular in that era.

Bobby said that, excluding one high school reunion that he attended at the John Sevier Hotel, he has never been back in the building. He cherishes the memories of his work experience at the old hotel.