The late Otto Burgner opened a memorable eatery about 1954 at 925 W. Market that he dubbed the Dutch Maid Drive-In. It quickly became a favorite of locals and handled the culinary needs of the area for 31 years.

I became a regular of the popular spot, driving my dad’s 1954 blue and white Chevy there. A cruise through its parking lot on Friday or Saturday evenings revealed a crowded parking lot full of 50s cars of every make and price. Those were the days of thirty-five cent hamburgers, dime soft drinks and dollar fried shrimp platters.

One notable food item on the menu was “Pizza Pie,” which Burgner is credited for pioneering for area restaurants. His “pie,” which he alleged to be the best tasting in the area, contained seven different cheeses. He also introduced the “Jumbo Burger,” while other restaurants were still dispensing small hamburgers.

Over time, the Dutch Maid ran the gamut from a popular teenage hangout to a well-liked senior adult morning gathering place. The end came at precisely 3 p.m. on Sunday, February 24, 1985. Demolition crews soon began methodically razing the once popular hangout to make room for another business.

Johnson City Press-Chronicle writers, Brad Jolly and Tina Hilton Chudina, covered in two separate articles the demise and destruction of the long-standing restaurant. The closing was a solemn occasion for Otto that brought back 31 years of mostly pleasant memories, which he related to Ms. Hilton in an interview shortly before the restaurant closed:

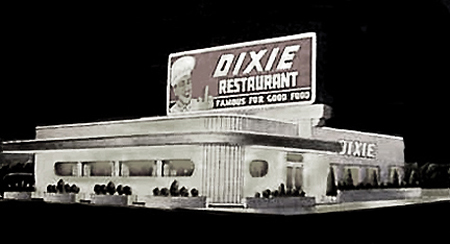

“Boys used to come and sit to watch girls and girls used to come and sit to watch boys. I’ve made a lot of friends here; it’s like losing part of the family. You just don’t walk out of a place like this without fond memories. Many married couples that come here today met here years ago. A lot of local doctors and lawyers that used to come here when they were kids now bring their families here. Times have certainly changed haven’t they? Competition was tough back then when there were several area restaurants that offered similar food such as the Dixie Drive-In, the Spot No. 1 and the Texas Steer Drive-In. I can remember when kids used to circle those three places. They had traffic blocked from here to the light at Market and Hillcrest streets. Business is still good, but the time has come for me to close.”

In latter years, the Dutch Maid’s hours were reduced to only breakfast and lunch. One of the trademarks of the place was the relaxed friendly atmosphere; people would eat breakfast there or just drink coffee and end up staying all morning.

Brad Jolly experienced the shock of seeing the rubble of the old restaurant: “I should have been prepared for it since we ran an article that it was going to happen. I just didn’t think it was going to be so soon. But Monday as I rode with a couple of colleagues to lunch, I saw the partially decimated Dutch Maid building. Bricks were scattered in the parking lot and gaping holes in the walls let harsh sunlight into the former dining room, the site of countless biscuit and gravy breakfasts and leisurely conversations. The unique décor with its wall-mounted stuffed fish and animals was now a mere memory. The loafers who used to kill time there over multiple cups of coffee were elsewhere, presumably wandering the city in a daze, cut loose from their familiar morning meeting ground.”

The Dutch Maid Drive-In became yet another trendy relic of yesteryear that appeared on the local scene, performed its job admirably and then quietly vanished, leaving behind only warm reminiscences.