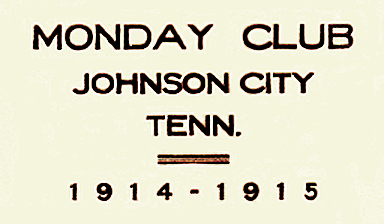

A 36-page booklet titled, “Monday Club, Johnson City, Tenn., 1914-1915,” contains a wealth of information about this longstanding impressive organization.

The society’s roots can be traced to 1892, when 11 area women formed “The Ladies Reading Circle,” a club devoted to the reading and discussion of books. The members initially met in each other's homes. Within a year, this group became known as “The Monday Reading Club.” In 1895, the same year the Johnson City Public Library was established, they shortened their name to “The Monday Club.” The federation’s stated goal was “the upbuilding and support of the Mayne Williams Library.” Striving for “Unity of Purpose,” they adopted the motto: “In good things, unity; In small things, liberty; In all things, charity.”

Feb. 6, 1913 proved to be a pivotal day for Johnson City when the society received a letter from local attorney, Samuel Cole Williams, donating property adjacent to Munsey Memorial Church and a $10,000 contribution to help build a new public library. Fulfillment of the club’s dream for a permanent home occurred on Jan. 1, 1923 when Mayne Williams Library opened its doors to the public. Prior to this, the library had occupied ten separate locations.

The club’s avowed pledge was to work toward better homes, schools, surroundings, scholarship and lives; to work together for civic health and civic righteousness; to preserve forests, and natural beauties of the land; To procure for children an education which fits them for life; to train the hand and heart as well as the head; to protect children who are deprived of the birthright of natural childhood; and to obtain right conditions and proper safeguards for women who toil.”

The officers for 1914-1915 were Mrs. Ferdinand Powell, President; Mrs. G.L. Smith, Vice-President; Mrs. O.E. Kizer, Second Vice-President; Mrs. R.W. Martin, Recording Secretary; Mrs. S.N. Hawes, Corresponding Secretary; Mrs. W.J. Barton, Treasurer; and Mrs. E.A. Long, Federation Secretary.

The club was divided into 11 departments with a director over each: Art (Mrs. W.P. Harris), Civics (Mrs. E.M. Slack), Civil Service Reform (Mrs. E.W. Kennedy), Conservation (Mrs. W.J. Barton), “Education (Mrs. C.E. Rogers), Mountain Settlement Work (Mrs. O.E. Kizer), Industrial and Social Conditions (Mrs. F.B. St. John, Literature and Library Extension (Mrs. G.L. Smith), Legislation (Mrs. L.A. Pouder, Public Health (Mrs. E.T. West) and Home Economics (Mrs. P.M. Ward). Club membership in 1914-1915 was 69 (48 active, 5 associate and 16 honorary). Annual dues for active members were $3.00.

After the much-anticipated new learning facility became operational, it opened on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, 1-4 pm between November 1 and March 31 and 1-5 pm from April 1 through October 31. The club met every Monday afternoon at 2:00 from the first Monday in October to the first Monday in April, the last one being their annual meeting. The following abridged departmental agendas for the meetings between Oct. 5, 1914 and Apr. 5, 1915 show an extraordinary diversity of scholarly subjects:

Oct. 5, 1914, Inauguration Day: Outgoing address by retiring president, Mrs. F.B. St. John; Talk – “Our Plan of Study.”

Oct. 12, 1914, Conservation: The New Forest Reserves and Irrigation in the United States.

Oct. 19, Public Health: A Free Clinic in our Public Schools, The Value of an Open Air School and Free Lunches.

Oct. 26, Legislation: The Relationship Between National and State Legislation and Tennessee Laws Relating to Marriage and Divorce.

Nov. 2, Industrial and Social Conditions: Public Address by Ernestine Noa of Chattanooga. A tea social followed.

Nov. 9, Modern Literature: Reminiscent Stories of American Humorists; American Wit and Humor; Readings from James Whitcomb Riley and Eugene Field; and Readings from ‘Mark Twain.”

Nov. 16, Modern Literature: The Development of Drama; Brief Sketches of the Life and Works of Hendrick Ibsen, Bernard Shaw, Maurice Maeterlinck and Edmond Rostand; and The Story of Chantecler.

Nov. 23, Modern Literature: The Social Message of the Modern Drama; The Children’s Theatre; Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Bjornstjerne Bjornson and James Matthew Barrie.

Nov. 30, Special Lecture: Edwin W. Kennedy, Professor of History, East Tennessee State Normal School.

Dec. 7, Home Economics: Modern Problems in the Home; Conservers and Destroyers of the Home; and A Balanced Dietary.

Dec. 14, Better Babies Day, Home Economic, Public Health and Conservation: The Community’s Responsibility Toward the Child as Regards to Birth, Environment and Instruction.

Dec. 20-28, No meetings due to the Holidays. (“Heap on more wood: the wind is chill; But let it whistle as it will, We’ll keep our Christmas merry still.” – Scott).

Jan. 11, Evening Reception with “The Play.” (“Tis the season for kindling the fire of hospitality in the hall, the genial fire of charity in the heart.” – Irving).

Jan. 25, Woman’s Day: The Contribution of Women to Science and Art; Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton and Jane Adams; and “What is the Ideal Life for Women?

Jan. 4, 1915, Art: No stated agenda. (“Art is the child of nature, yes, her darling child, in whom we trace the features of the mother's face.” – Longfellow).

Jan. 18, Civil Service Reform: Five-Minute Reports on Local Conditions in Public Schools (The Appointment of Teachers, To Whom Responsibility and How Removed and The Condition of School Buildings).

Jan. 25, Woman’s Day, Agenda: The Contribution of Women to Science and Art; Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton and Jane Addams;

Feb. 1, The Mayne Williams Library: Program by Library Directors.

Feb. 8, Mountain Settlement Work: Our Mountaineers.

Feb. 15, Modern Literature: The Development of the Short Story; The Place of the Short Story in Modern Literature; and Selected Readings from Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Nelson Page.

Feb. 22, Travel – Mexico: Historic Mexico and Mexico Today.

Mar. 1, Modern Literature: Modern Poets and Poetry; America’s Contribution to Poetry in the Last Half Century; and Readings from Representative Modern Poets – John Masefield and Alice Meynell.

Mar. 8, Modern Literature: Special Characteristics of Southern Poetry and Selected Readings from Poe, Lanier, Ryan, Hayne, Dunbar and Keller.

Mar. 15, Education: The New Education, What Shall We Keep?; Woman as an Educator; and Discussion – What May We Do As Mothers to Aid the Teaching of Our Children?

Mar. 22, Civics: Some Modern Methods of Making Living Conditions More Wholesome; The Origin and Benefits of the Organization of Housewives League; and Churches and Schools as Social Centers.

Mar. 29, Travel – Panama, Agenda: The Story of Panama and How It Came into the Possession of the U.S.; The Panama Canal and Its Economic Value to the World.

April 5, Final meeting of the term. (“Farewell! A word that must be, and hath been – A sound which makes us linger; – yet-farewell” – Byron).

According to Mrs. Mattie Mullins, former club president, the organization orchestrated numerous improvements throughout the years: “The beginning of garbage pickup in Johnson City, paying for boys and girls to go to the clinic at ETSU to have their tonsils removed, serving hot lunches in the public schools beginning at the old Columbus Powell Elementary School and planting flowers and bulbs in the city early each spring in such places as Fountain Square and churchyards and library.”

Some 115 years later, the Monday Club, Monday Club Auxiliary and Junior Monday Club continue their long established support of the beautifully designed and functional Johnson City Public Library. Today, the Monday Club, with approximately 240 members, meets the first and third Mondays of each month (excluding the summer months) at the library.