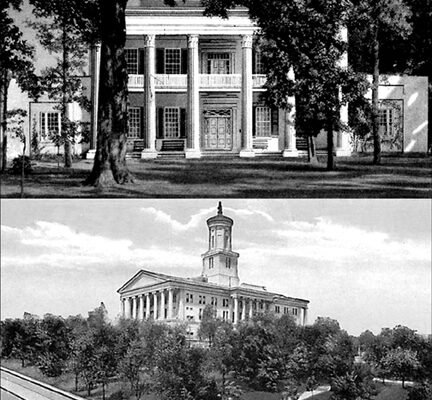

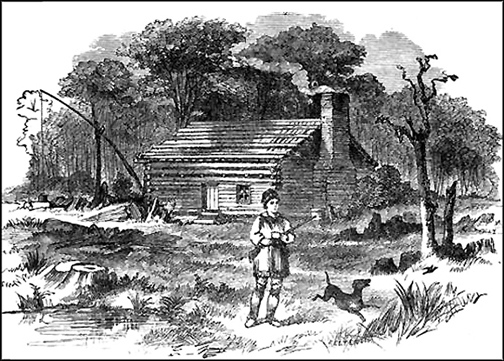

Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States, once practiced law in Jonesborough and Greeneville, residing there for several months in the Christopher Taylor log cabin. He became a polarizing and dominating political figure in the 1820s and 30s who ultimately helped shape the modern Democratic Party.

In January 1915, Andrew Jackson Day was celebrated in Nashville, Tennessee. The Andrew Jackson Memorial Association and the Ladies' Hermitage Association (LHA) were the primary movers in organizing a massive downtown celebration.

One significant portion of the event was to unveil a newly constructed statue as a memorial to “Old Hickory,” paid for from a vast network of local agencies and public contributions. The LHA was praised for their efforts in saving and preserving Jackson’s home place, thereby establishing a model for how preservation of antiquities should be handled.

The day began with a festive parade that organized at Broadway and Eighth Avenue at 10 a.m., moved through the principal streets of the downtown business district to Capitol Boulevard and on to the State Capitol. In the procession were representatives of military, municipal, and patriotic organizations. Along the west side of the Capitol Boulevard behind many bales of cotton, two companies of Confederate soldiers engaged in a mock battle using personnel from two companies of the Tennessee National Guard.

At the conclusion of the reminiscence of the Battle of New Orleans, several young ladies, acting on behalf of the LHA, released several white doves as a token of peace. Upon the Capitol Boulevard, a great throng of spectators heard public addresses from Governor Ben W. Hooper, Major E. B. Stehlman, and Judge S. F. Wilson.

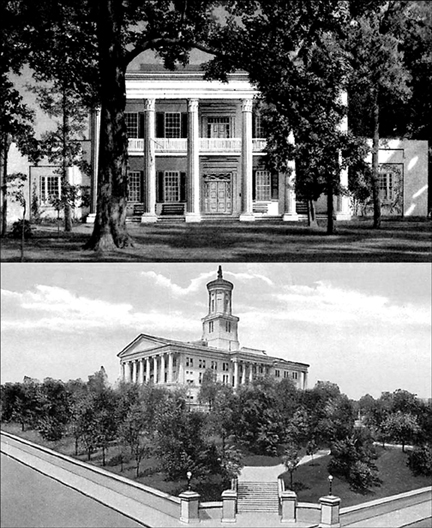

The most impressive ceremonies of the morning were held on the east side of the Capitol under the auspices of the LHA. Here the equestrian statue of General Jackson was decked with wreaths of flowers that had been placed upon it with appropriate remarks by ladies representing the various patriotic organizations. Judge Wilson, Regent of the LHA, delivered the principal address. On the same afternoon, a hickory tree was planted at Centennial Park in Jackson’s honor.

That evening, about 200 citizens attended a banquet at the historic Maxwell House. The toastmaster, Mr. Robert L. Burch, introduced seven prominent speakers. Later, a dazzling ball was held at the Hermitage Hotel.

The next morning, the Daughters and many invited guests made a pilgrimage to the tomb of Andrew Jackson at the Hermitage. The burial place had previously been appropriately decorated. Several speakers were introduced. One lady gave an interesting personal reminiscence of General Jackson and read an affectionate and treasured letter written by the general to her mother. Another person told some incidents of the attack on Baltimore by the British and the defense of Fort McHenry. The originator of the pilgrimage spoke to a group of school children from Old Hickory School, reminding them of Jackson's work in the Indian warfare of the southern country.

Finally, two wreaths of evergreen gathered from the old church that had been built in 1823 by Jackson for his wife, were placed upon the graves of General and Mrs. Jackson. After these exercises and a luncheon, the final speaker presented a paper dealing with Jackson’s storied career.

This brought to a close a day enjoyed to the fullest by a deeply interested and appreciative audience. It was a fitting tribute to a fitting man – Andrew Jackson.