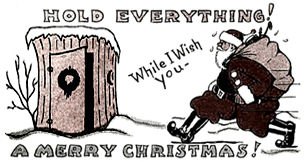

In 1965, songwriter and recording artist, Billy Edd Wheeler, hit the pop charts with the novelty tune, “Ode To The Little Brown Shack Out Back,” referring to outhouses. In the amusing song lyrics, Wheeler begs for the traditional little brown building to be spared its rapidly approaching demise.

Many Johnson Citians can recall these little icons of the American backyard, affectionately dubbed by additional names as privy, necessary house, shanty, backhouse, throne and john. The little pine shed with its sloped roof was about 4x4x7 feet, positioned over a hole that was 4-5 feet deep. A quarter moon cutout along the top of the door allowed some light and ventilation.

Outhouses stood about 100 feet behind a family’s primary residence, which in the winter was 100 feet too far (bitter cold), but in the summer was 100 feet too near (lingering fragrance). The specified distance was a decided compromise. The average privy was a one or two “holer.” Some had one seat for adults and another modified for toddlers. Those at churches, schools and public places had additional amenities to handle crowds.

A Sears and Roebuck catalog was a standard fixture inside an outhouse, but the number of pages in the big book seemed to decrease with each passing visitor. Also present in many backhouses were spent corncobs and a bucket of lime. Every 1-2 years, the evocative little shack needed to be moved and centered over a nearby freshly dug pit. The old hole was promptly covered and packed down with dirt from the new one.

Most outhouses were unpainted and seemed to unassumingly blend in with the surroundings. The little sheds became the targets of Halloween pranksters who would move them, sometimes with some poor hapless soul sitting inside. Others would have signs painted on them that read “Sitty Hall,” “Half Moon Inn,” “Rest Home” and “The Establishment.” People learned to keep the door closed when not in use. Many a hound dog found solace from adverse weather by curling up inside a privy with an opened door.

Slop jars, or chamber pots as they were alternately called, were used in tandem with outhouses. These were three-gallon metal pots with lids that conveniently sat at night under the bed or in a nearby closet. A person waking up in the middle of the night with that certain urge had a decision to make. He or she could go to the privy outside or utilize the slop jar inside. Choosing the privy meant exiting the house and traveling to the john in the darkness of night and whatever weather conditions might exist. This choice occasionally resulted in a chance encounter with a mouse, rat, snake spider or even a colony of ferocious bees or hornets. Conversely, selecting the slop jar at night meant having to “live with it” until morning, after which it had to be taken outside, emptied, cleaned and dried for the next night's exploit.

The universal desire for in-house facilities led to numerous patents over the years, including several from 19thcentury Chelsea, England plumber, Thomas Crapper. (I am not making this up.) Billy Edd Wheeler’s worst fears in the song were realized when health regulations outlawed the familiar little sheds, leaving behind a lingering thick green vegetated plot of land.