Andrew Johnson Stover was a grandson of Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States. As a child, he frolicked about the White House and lawn and became a favorite of the political brass of his day. His lifestyle later changed dramatically when he left the nation's capital to became a hunter and a trapper, dwelling in a rudimentary log house insulated with clay in the Holston Mountains of East Tennessee.

To look at Stover as an adult, one would think that he had always dwelled in the environment that he later occupied. Even though he dressed like and mingled with other mountaineers on occasion, he preferred to be alone.

The grandson had been eyewitness to some stirring events in American history, happenings in which the central figure was his grandfather. Although some individuals had made the transition from a log cabin to the White House, few had abandoned White House living to return to a wilderness mountain abode.

Yet, such was the history of Andrew Johnson Stover, whose grandfather succeeded the great Abraham Lincoln and whose biography was itself eccentric and interesting. Not many men occupied the White House whose life story was as romantic as that of Andrew Johnson. And few have spent their boyhood in the White House and their manhood as a frugal mountain hermit in a log hut like the president's grandson.

In the little town of Greeneville, Tennessee, stood a rude structure, gray with age, over the door on which was a weathered stained sign upon containing the letters, “A. Johnson, Taylor.”

In the ancient structure of his early youth, Andrew Johnson piled the needle and handled the goose; he made the long-tail coats and fancy trousers for Greeneville dudes of that era. Likewise, he cut and sewed the more sober garments for deacons and judges in the village.

So, with Andy Johnson, cross-legged on the tailor's bench, the little shop became a sort of political forum for the community. While men were measured for a new Sunday outfit, they were surprised to see what a wonderful grasp of public awareness their tailor possessed.

And while the future president's needle was busy basting suits for the Greeneville beaux, the loom of fate was busy weaving another fabric, which Andrew Johnson was to sew into one of the most spectacular careers in American history.

Step by step, he rose in life until he became Vice-President of the United States and when the great Abraham Lincoln was silenced by the bullet of John Wilkes Booth, the Greeneville tailor succeeded to the chief magistracy of the nation.

A fate uniquely awaited him as an occupant of the White House. In his horizon was an impeachment trial with which he would have to grapple.

What was Mr. Stover doing while the throng of hostile critics took unpleasant aim at his grandfather? All this occurred while the world was looking curiously on to see what sort of political pathology would be applied to the ghastly wounds in the American Union. Stover continued playing in the White House and on White House grounds.

Those were not the most brilliant days, socially, the White House ever knew. The country was just catching its breath after a prolonged and ghastly war in which the Union had seemed at times to be in danger of being forever split. It was a time when countless homes had been saddened and desolated and thousands of brave men had been killed or wounded on many bloody battlefields.

Nevertheless, there was a certain relief and joy in all hearts that the war was over and this feeling found expression in the society affairs of the time. There was a cheerfulness and exuberance about them unknown for some years past.

At any rate, Stover saw the most splendid society of that era at its brightest. He had total freedom in the White House as he observed foreign representatives in their gold-laced uniforms and breast bedecked with royal orders. He saw the loveliest women of this time flaunting in gauze and crinoline in dreamy waltz. He watched with uncomprehending childish eyes the great events that succeeded each other with such startling rapidity.

Perhaps he comprehended more than any one guessed. Maybe he saw the hollow emptiness of glory and grandeur. Possibly, in those childish days at the capital, a sort of infantile philosophy taught him the misery that goes hand-in-hand with political distinction, the heavy cares, the responsibilities, the heart aches and the weary burdens. Perhaps he determined then, in his boyish heart, to turn his back on all of that and seek happiness in the simple life close to God's creation.

At any rate, the White House child soon became a log cabin man. The magnificence of the executive mansion was succeeded by the rustic walls of a cabin set in a mountain of wilderness.

The formal White House gardens were succeeded by the rugged wilderness of the mountain slope, decked in tangled green, save in mid-spring, when the dogwood and other mountain flowers were in the glory of full blossom.

Andrew Johnson's Grave, Andrew Johnson Stover, Taylor Shop in Downtown Greeneville, TN

Instead of sitting on his knees in the councils of this and other nations, Andrew Johnson Stover had for his companions his guns, his dogs, his traps, the sunlight, the shadow, the pine tree, the raccoon and the hoot-owl. Beside a mountain brook, clear and sweet, bubbling and splashing downward to the valley, he had no vain regrets of giving up his previous days. The free wild mountains and the blue, overarching sky, were more pleasant to him than the stately gardens at the nation's capital.

Andrew Johnson was likely chosen for the vice-presidential nomination because he was a Tennesseean. He was well-known. His name was conspicuous among the politicians of the war period, not only because of personal abilities, but because he was a Union Southerner. His geographical location made him a valuable running mate for Lincoln.

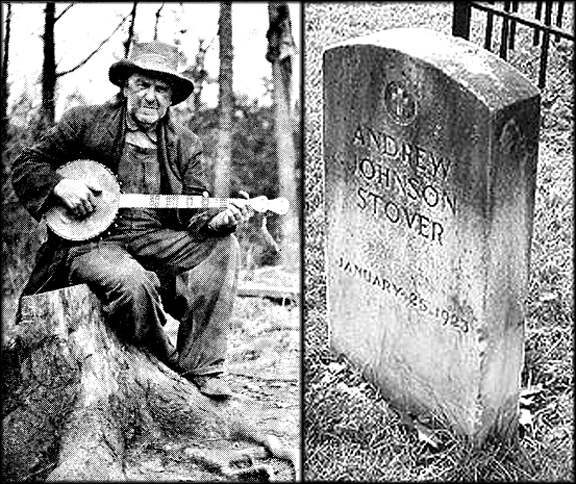

Andrew Johnson Stover Plays the Banjo. A View of His Final Resting Place

Andrew Johnson Stover was excited neither by recollections of his childhood in the White House nor the work of the landscape gardener in the country around his grandfather's grave. His gun and his cabin in the mountains were all that he asked for in life. But to the ardent student of human nature, both Andrew Johnson, the president, and Andrew Johnson Stover, the hermit, are well worth studying. The unique journey will be rewarding.