The Liberty Theatre was the smallest and least pretentious motion picture theatre in Johnson City, yet the most evocative to area B-western movie fans. In the early to mid 1950s, patrons could enter the establishment at an affordable price (nine cents for children, fifteen cents for adults), consume a soft drink for a nickel, and munch on a big box of the best tasting popcorn on the planet for a dime, all the while being treated to a suspenseful cliffhanger serial, animated cartoon, newsreel, and an action-packed cowboy flick.

Moviegoers once had five downtown theaters to satisfy their voracious big screen appetites. The Majestic (239 E. Main Street) and the Sevier (113-117 Spring Street) featured the latest contemporary upscale movies. The Tennessee (146 W. Main Street) and Liberty (221 E. Main Street) showed second-run movies, focusing heavily on budget pictures, “shorts” and serials. A fifth theatre, the Edisonia (236 E. Main Street), projected silent and early “talkie” movies, later becoming known as the Criterion and the State.

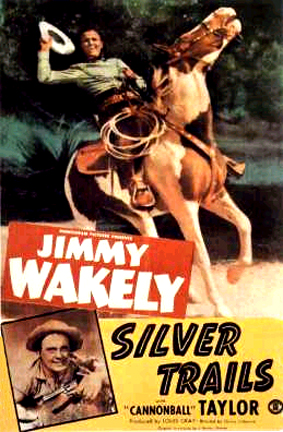

An afternoon of thrilling entertainment at the Liberty Theatre began with a newsreel, followed by previews of “coming attractions,” advertising such film celebrities as Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, Rex Allen, Hopalong Cassidy, Johnny Mack Brown, Sunset Carson, Wild Bill Elliott, Allan Rocky Lane, Tex Ritter, Jimmy Wakely, and “Lash” LaRue. Next, a cartoon was shown featuring the antics of such animated characters as Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Popeye, Tom and Jerry, Yosemite Sam, the Roadrunner, Tweetie and Sylvester, Woody Woodpecker, Droopy, and others.

Afterward, the next much-anticipated “chapter” of the featured serial was presented. This was a unique and clever film genre presenting a central plot in an episodic format of 12 to 15 installments, each about 17 minutes in duration. At the finale of each serial, the heroes appeared to die from one of an inexhaustible list of calamities: animal attacks, train wrecks, falling boulders, poisonous darts, burning buildings, airplane crashes, explosions and cave-ins. Each one concluded with such words as “To be continued… at this theatre next week.” The intent was to bring people back, no matter how busy or sick they were, at additional cost, to find out how their brave superman miraculously escaped impending death. It always worked.

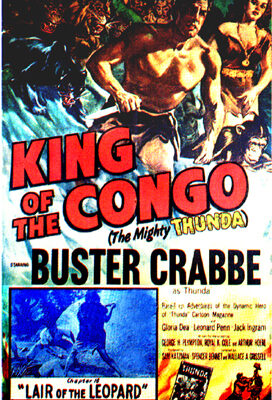

The management frequently gave patrons a card with numbers that corresponded to each chapter of the current serial. The attendant would punch it with each visit, awarding free access to the theatre for those who arrived for the final chapter with a fully punched card. Area aficionados can still recall many of the 231 “talkie” serials, including “King of the Rocket Men” (Republic, 1949, 15 chapters), “Captain Video” (Columbia, 1951, 15 chapters), “Thunda, King of the Congo” (Columbia, 1952, 15 chapters), “Radar Men From the Moon” (Republic, 1952, 12 chapters), and “The Lost Planet” (Columbia, 1953, 15 chapters).

With the preliminaries out of the way, the fans were now ready to sit spellbound on the edges of their seats for about an hour of hard riding “shoot-em-up” western action. B-western movies had a recurring theme; a slick cowboy would mysteriously arrive to thwart some bad hombres from taking a fair damsel’s ranch, usually located on a proposed railroad line or containing a bed of rich deposits of oil or gold. With this western genre, the actions were quite predictable, and the final outcome was never in doubt. The good guys always triumphed over the bad ones; there were no exceptions.

A western film needed three things to be successful: an imposing hero, a faithful horse, and a funny sidekick. If a movie got too serious, the comedic sidekick was always ready to inject humor into the story line. Notable cowboys/sidekicks included Roy Rogers/”Gabby” Hayes, “Lash” LaRue/Al “Fuzzy” St. John, Gene Autry/Pat Buttram, Jimmy Wakely/Dub “Cannonball” Taylor, Charles Starrett (the Durango Kid)/“Smiley” Burnette, and Johnny Mack Brown/“Fuzzy” Knight. Western fans were equally familiar with their hero’s horses. Who could ever forget Allen’s Koko, Autry’s Champion, Cassidy’s Topper, Brown’s Rebel, Carson’s Cactus, Elliott’s Thunder, Lane’s Blackjack, Ritter’s White Flash, Rogers’ Trigger, Starrett’s Raider, and Wakely’s Sonny? A good horse not only provided its rider with reliable transportation, but also could be called upon to lend a hoof when needed in a precarious situation.

This genre displayed a slightly different flavor when singing cowboys the likes of Tex Ritter, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Jimmy Wakely, and Rex Allen rode across the big theatre screen carrying guns and guitars, proving to their loyal fans that real men could both fight and sing. Moviegoers marveled when those serenading cowhands rode their beautiful stallions over extremely rough terrain, bouncing around in their saddles, yet singing a song so smooth and perfect it appeared to have come from a recording studio (which it did).

A cowboy would courageously fight the most loathsome villain one moment only to sing to his horse the next in the fresh air of the open prairie, thinking about that pretty cowgirl waiting for him at the end of the long winding trail. This was romanticism at its very best. A fundamental rule of B-western films was that cowboys could not kiss their favorite girls, at least on the theatre screen. That was a definite violation of the “code of juvenile expectancy.” The youthful crowd would permit their heroes to kiss their colorful horses but never their favorite ladies. At the movie’s finale, youngsters would file out of the theatre, trek back to their homes, saddle up their old broomstick broncos or living room rocking horse chairs and continue the adventure in the privacy of their own residences, receiving a bonus for the money they had spent.

Sadly, the 1950s slowly brought down the big curtain on B-western movies, caused by escalating production costs and the arrival of television into homes. The studios were reluctant to bring in a fresh crop of eager actors to replace the now aging ones. Thus, the Liberty’s final chapter was fast coming to an end. The theatre closed its doors about 1956 after twenty-seven years of operation. The modest and popular organization mounted its big golden palomino, “Popcorn,” and gracefully galloped into the sunset, never to return. Avid cowboy fans were saddened as they watched their favorite downtown establishment give way to a lady’s dress shop — the New Vogue… without so much as a cowboy hat, chaps, boots, or saddle to be found on the premises.

The now aging B-western film fans must sit back and be content with the memories of hundreds of Saturday afternoons spent watching their favorite saddle aces, most of whom are long deceased. Watching an old western movie on television today does not afford the same exhilarating thrill once experienced when kids crowded into the small Liberty Theatre, gazing intently at the screen and cheering their favorite heroes. Will the day of the B-western ever return?… Probably not!