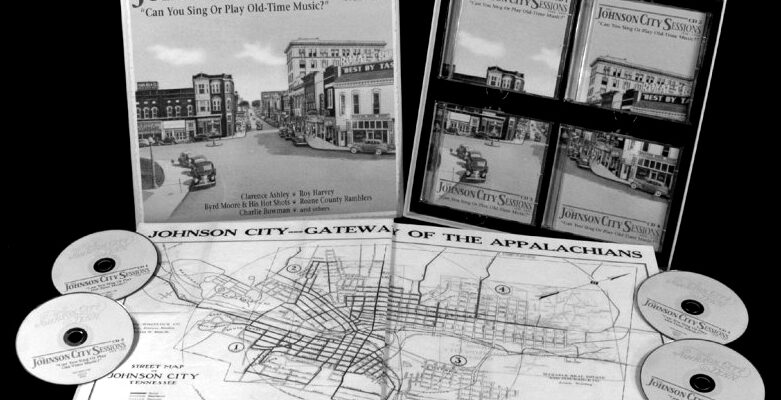

John Thompson recently wrote an article for the Press concerning Nicholas (“Nick, the Hermit”) Grindstaff (1851-1923), a celebrated legend of yesteryear who spent most of his adult life in solitude on 4,000-foot Iron Mountain in Johnson County. My aunt, Doris Cox Anderson, reminded me that Nick was her husband Dana's great uncle. He shared added facts about his kin.

One item was a 1939 26-page booklet titled, “Nick, The Hermit: A True Story Written in Poetic Form of Nick Grindstaff, Johnson County, Tennessee – 'The South's Most Famous Hermit.'” It was compiled by Asa Shoun (a friend), R.B. Wilson (a relative) and D.M. Laws (a professor). It contained an epic 693-line poem that was magnificently composed in rhyme in 1926 by A.M. Daugherty, known as the “poet laureate of Johnson County.”

Nick's life story is an engrossing one. After losing both parents, Isaac and Mary Heaton Grindstaff, at a young age, he was raised by relatives until he was 21 years old. By then, he was strong, handsome and intelligent. Soon, Uncle Nick, as he became known, inherited one-fourth of the family property where he resided until 1877. At age 26, he sold his land and relocated to the West to seek his fortune, becoming a successful sheep herder. His yearning was to set aside enough money to return home and seek a bride.

After six years, Nick headed back to his beloved East Tennessee mountains. While en route, he became victim of a robbery, losing his belongings and the cash he had set aside. During the scuffle, he received a severe blow to the head. There are several variations to this account, one involving a woman who tricked him. When Nick arrived on Stoney Creek, family and friends quickly noticed a significant change in him. He began shunning people and displaying a strong desire to live in seclusion. Nick, by some means, was able to acquire 50 acres of land on top of Iron Mountain, along Richardson Branch just out of Buladeen and made it his private living quarters.

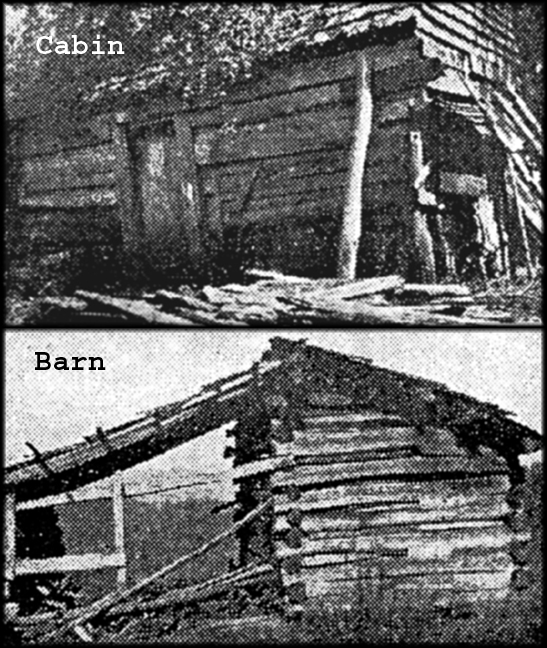

Grindstaff built an 8×8 foot log cabin with a rock and mud fireplace under a large hickory tree that provided ample shade in the summer. Reportedly, the home's only entrance door measured 18 inches wide by three feet high, a peculiar size for a stocky man. There were no windows to let in daylight or to afford a panoramic view of the outside. Nick carefully sealed small openings and cracks in his shack to deny entry of small varmints and to protect him against the harsh elements. The hermit's next task was to build a small rudimentary barn.

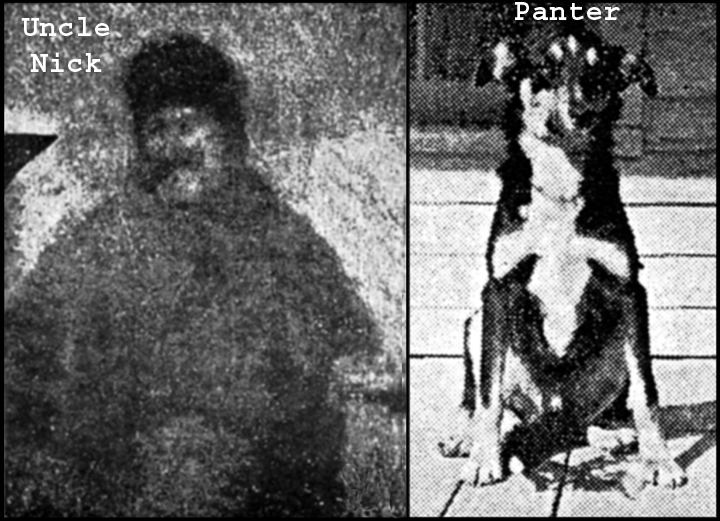

Even in his solitude, Uncle Nick was not entirely alone. In addition to the usual wild animals that occasionally drifted onto his property, he owned a cow, an ox, a faithful dog named Panter and even a pet rattlesnake that surprisingly roamed freely inside his cabin. The hermit's animals, wild and domestic, were special to him because they lived together as a family in peace forged by a common partnership in survival.

The thick mustached solitudinarian cooked over a fire and slept on a split log slab on a dirt floor. He cultivated a small tract of land and farmed a little, which included handovers (rutabagas). He also harvested yellow apples, which he stored in a hollowed out chestnut stump that was about five feet high and five feet in diameter, large enough to hold 10 bushels of the succulent fruit. Neighbors fondly recalled how good they smelled when he lifted the lid on the stump.

In addition to farming, the rugged mountaineer kept his two buildings in good repair, as well as building and repairing fences that surrounded his abode. His few basic tools included a double-edged ax, which he put to good use.

A neighbor, who bore the name of “Bear Hunter” Sam Lowe, once went to see Uncle Nick. As he approached the house, he heard a loud rattling sound inside, which he readily identified as a rattlesnake. As he raised his gun to destroy it, Nick halted him and ordered him to leave it alone. Apparently, Sam was unaware that the snake was his pet who slept in the rafters close to the fireplace and enjoyed a hissing good time in isolation. After Nick stepped away for a couple minutes, he heard a loud bang and returned to find his lifeless favorite reptile on the floor. He mourned for some time over the loss of his poisonous partner, thereby becoming even more resolved to subsist as a hermit.

Nick always kept a loaded gun handy to fend off unwanted visitors who stumbled upon his habitat. Once in a while, he trekked down the mountain to the valley where he did chores for folks who paid him wages. He used the money at a local store to purchase groceries, such as coffee, meal, bacon, tobacco and other sundry supplies. The trip also afforded him the opportunity to get a haircut.

Sporadically, Nick would arrive unannounced at a neighbor's residence about suppertime. In those days, it was considered poor manners not to invite someone to eat with you if he or she came to your house at mealtime. Although the hermit never asked for a handout, he usually got one. After finishing a meal, he would abruptly leave, often without uttering a word of appreciation. People did not consider him rude; they understood this gentle woodsman.

On July 22, 1923 at the age of 71, Nick the Hermit passed away in his sleep. That summer he had just put up a patch of sugarcane that he planned to use to make molasses but departed this life before it was time to harvest his crops. When a neighbor found him, he appeared to have been dead an estimated four days, apparently from natural causes. His friends had a difficult time getting Panter out of the house because the animal sensed something was wrong and was not about to let anyone near his master. Finally, they were able to contain Panter with a rope and remove Nick's body from the cabin.

After preparing the hermit for burial, they placed him in a nice coffin that had been paid for by family and friends. Legend has it that they allowed Panter to lay on his chest during the viewing. The dog seemed to know that his owner was gone because he howled mournfully. More than 200 people showed up at Nick's funeral to bid him farewell. It was said that Panter never got over Nick's passing and became so aggressive at times that he eventually had to be put down. His body was appropriately buried at Nick's grave.

Two years transpired. On July 4, 1925, R.B. Wilson, with the help of Nick's relatives and friends, erected a sizable monument, located 200 yards from where his cabin stood. It was fabricated from cement and mountain granite, along with a slab of marble purchased from the Mountain City Marble Company. The memorial cost $208.07 and was constructed by Vaughn Grindstaff and Asa W. Shoun. The simple wording on it best described the hermit's life: “Uncle Nick Grindstaff – Born December 26, 1851 – Died July 22, 1923 – Lived Alone, Suffered Alone, Died Alone.”

Ironically, the marker was situated on land that would soon become a part of the expanding Georgia to Maine Appalachian Trail. One can only imagine the number of hikers throughout the years who have paused at his monument to rest.

Residents from nearby counties gathered at Uncle Nick's new monument to hold a memorial service. Many distinguished people were present, including Judge S. Earnest Miller (an attorney who practiced out of the Masengill Building at 242.5 E. Main in nearby Johnson City). The service was noted as follows: First Music – “America”; First Speaker – Asa W. Shoun, speaking on “The Life of Nick”; Second Speaker – J.M. Stout on “The Life and Character of Uncle Nick”; Funeral Sermon – Address by Rev. R.M. DeVault; and a lecture – by Prof. D.M. Laws.

For people who today live in the valley between Holston River and Iron Mountain, the name of Uncle Nick Grindstaff evokes hand-me-down memories of a mountain spirit that has long vanished. The folks around Buladeen along Stoney Creek Road still talk about him through stories that include those that are accurate, mildly embellished or in part distorted. Nevertheless, Nick the Hermit was a unique person.

As John Thompson noted in his article, Granville Taylor, a nephew of Uncle Nick, has established a fund to restore Nick's crumbling grave marker. You can contribute by contacting him at (423) 474-2010.