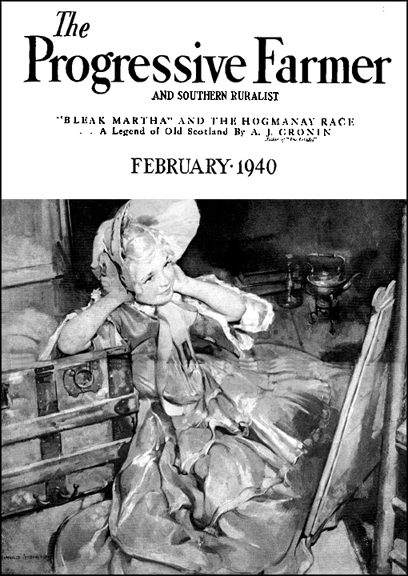

During my youth, I recall seeing a magazine titled, “The Progressive Farmer” lying around in some of my relatives’ country homes. I loved to glance at the ads in it. Today, I occasionally purchase one at a flea market, antique store or auction and I still enjoy its dated contents.

Today’s column photo is from the February 1940 edition. Reading it is a nostalgic trip down memory lane. Allow me to paraphrase comments from selected ads:

Prince Albert tobacco evoked a special memory for me. Some of us pranksters phoned grocery stores and asked the attendant if he or she had “Prince Albert in a can?” The response was always in the affirmative. We then responded: “Well, you better let him out before he suffocates.” We then hung up. The tobacco was advertised as “Crimp Cut” to be used in long burning pipes and rolled (yes rolled) cigarettes.

In another ad, seven panels reveal a father trying to convince his young son to swallow some foul-tasting adult laxative. Mother soon comes to the rescue with a spoonful of Fletcher’s Castoria. The lad gleefully laps the spoon. Somehow, I do not remember it being that wonderful, but it definitely beat Castor Oil.

International Harvester’s new McCormick-Deering Farmalls introduced ‘Lift All,” the first all-purpose hydraulic air lift and ‘Culti-Vision,” with offset controls that gave the driver full view of his field. Four models were offered.

Plymouth offered a two-way guide to the best car value. Customers were urged to examine the quality chart for facts about the new 1940 vehicles and then take the luxury ride for proof. Plymouth’s rating that year was 21, the highest score among the other cars.

The Lifebuoy’s Health Soap ad proclaimed that hard work, exercise and even the lightest farm chores could bring on perspiration. To the rescue comes Lifebuoy; its crisp odor immediately disperses, leaving the bather with protection that lasts and lasts. I loved the smell of Lifebuoy in my youth and still do.

Ball Band Shoes were so-named because they had a black band around them. They were marketed with a big red dot with the words, “Look for the Red Ball.” They supposedly fit better, were more comfortable, resisted wear and were more affordable than their competitors.

Lee Overalls is another one I recall. A Ripley’s “Believe or Not” entry that year stated, “If Lee overalls started marching today past your home 13 paces apart, they would march forever and no overall would pass your home twice.” Ripley explained why. “As fast as this line would march, new overalls being manufactured by Lee would maintain the line and the march would go on (indefinitely). The ad concluded with “If Lee overalls don’t last longer than any overalls you ever wore, Lee will give you a new pair free.” Believe it or not.

A&P Food Stores promoted their coffee line by joining thousands who saved on their three brands of coffee: Eight O’clock, Red Circle and Bokar. I don’t recall those brands.

Harley Davidson told farmers that owning a motorcycle offered many advantages: riding to and from school, performing farm errands quickly and economically and taking scenic vacations. Sending in a coupon brought a 24-page brochure featuring photos and stories from owners.

Tuxedo Starting and Growing Allmask guaranteed to keep farmers’ chicks healthy, allowing them to grow into well-developed pullets with high egg production. The product aimed at helping these birds withstand diseases induced by vitamin starvation such as nutritional roup, nerve disorder and rickets. The product’s empty bag could be used for making dresses, romper suits, draperies, furniture coverings, pillows and other useful articles.

Finally, the Bristol Chick Hatchery took out a small ad for Leghorns, Rocks, Reds, Irpingtons, Wyandottes, Hampshires, Giants and Cornish. Interested parties could write for an illustrated circular describing the products.

The thing that stands out in the publication is the low cost of products and services in 1940.