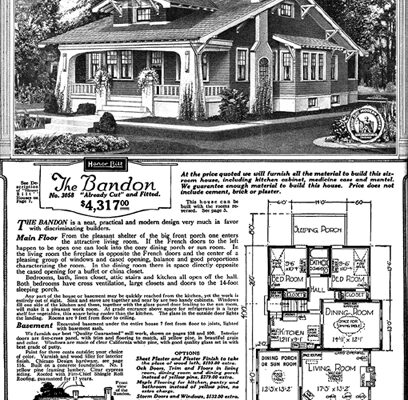

From 1908 to 1940, it was not unusual for a Johnson City family to anxiously travel to the railroad station to greet the arrival of their newly purchased mail order prefabricated model home from Sears, Robuck & Co. (formerly dubbed the “World’s Largest Store”).

On board were one or two railcars containing approximately 30,000 house components weighing an estimated 25 tons. During the program’s 32-year span, over 100,000 homes representing 447 styles were offered to the public. Entrepreneurs Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck began their successful business venture in 1893.

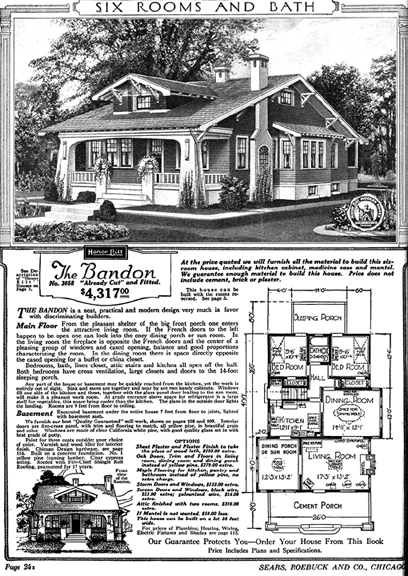

To order a prefabricated home, buyers had to show clear title to the lot, have steady employment and make a pre-payment equal to 2.5 percent of the amount of the material bill. A kit included all materials needed (excluding the house’s foundation) to build a sturdy, well-designed house. Eager homebuyers, aided by family, friends and neighbors, often provided labor for the project. Others contracted the work with a local construction firm or paid Sears to build it for them.

Each home came with an elaborate leather bound instruction manual containing step-by-step instructions for assembly. Sears promised that an average sized house could be constructed in about 90 days. A unique number inserted on each piece of carefully precut lumber identified its exact location as noted in the manual, eliminating any guesswork.

Sears Modern Homes consisted of three choices: Honor Bilt, Modern Bilt and Simplex Sectional. The first used only the best types of lumber, such as Douglas fir or Pacific Coast hemlock for framing, cypress for outside finish; and oak, birch and Douglas fir or yellow pine for interior finish. Catalogs showed floor plans ranging from modest to elegant homes. For instance, Honor Bilt homes in 1926 ranged from $986 (The Fairy) to $4909 (The Glen Falls).

Standard Bilt homes that ranged from $499 to $999 were available for those who could not afford the more expensive Honor Bilt ones. Although they too were high quality, they were not top of the line.

Simplex Sectional units were, as the name suggests, made in sections and could be quickly bolted together. These included add-on garages ranging in prices from $87 to $227. They also were suitable for summer cottages and hunters’ cabins.

Renters were urged to buy prefab homes and save monthly payments. The houses, depending on their size, could be paid off in as little as seven years. A side benefit of home ownership was having a nice yard where the entire family could enjoy landscaping it with green grass, flowers and vegetable gardens and a variety of trees, shrubbery and plants. Some house plans allowed potential buyers to alter the layout, such as reversing floor plans that took advantage of morning and evening sun. These altered plans contained the word “Reversed” after the name. Also, customers could suggest design changes by submitting blueprints to Sears, creating another kit.

As an experiment, the company once built two identical houses. One was built the ordinary way that required measuring and cutting; the other was a Sears home kit just as it came from the factory. The Sears home required 40% less labor. The company also sold wood to consumerswho chose not to order a precut home but desired quality materials from them at lowest cost.

In early years, houses could be built with or without an indoor bathroom. When one was included, it was generally located on the second floor. The company even sold a 720-pound sturdy outhouse kit priced at $41 that measured 4×7 feet. It contained ventilators on each side, asphalt roofing and two smooth finished seats with different size holes – one for adults and the other for children.

In later years, central heating, indoor plumbing, and electricity became standard in most homes. Consumerscould select the heating system that best suited their needs: hot water heat, steam heat, warm air heat and a Hercules “pipeless” furnace. Also available were complete plumbing systems and a choice of bathroom fixtures such as the little nostalgic porcelain tub that stood on four feet.

Consumers could pay cash with the order, pay for material during the construction phase, pay after inspecting the shipped material or provide a “guaranteed letter of deposit” from a post office. The latter stated that the buyer had deposited with them the required sum of money as a special fund to be paid upon delivery of the kit. Every home carried with it a “Certificate of Guarantee” for delivery of all materials as detailed in the plans and specifications.

A typical testimony from a satisfied homeowner reads as follows: “I am well pleased with the house and with your material. My wife and I, who are approaching 60 years of age, built the house ourselves and saved about $1,300.”

The curtains came down on the Sears Modern Homes era by the Great Depression of 1929. Almost overnight the company was thrown into a financial tailspin by steadily rising payment defaults. Because of their high quality, many of the homes are still standing. According to local resident, Ken Harrison, the houses at 309 W. Pine Street and 320 Hamilton Avenue in Johnson City are Sears homes.

The City of Johnson City Historic Zoning Commission is interested in learning of any Sears kit homes that are located inside the city limits. If you know of any, please call Jessica Harmon with the City of Johnson City Planning Division at (423) 434-6073.

How can someone identify a house as being a Sears one? Search the Internet for suggestions: “Determine if the house was built between 1908 and 1940. Compare the actual floor plan dimensions with those shown in an old catalog. Identify characteristic column arrangements on porches. Find a square block molding at the foot of stairs. Look for numbers on boards used in attics and basements. Locate a shipping label under a staircase. Find the house’s building permit in a local courthouse. Look for an “R” or “SR” on plumbing. Find a stamp that says “Goodwall” on the back of sheetrock.”

(Resources/contributors: www.searsarchives.com; www.wikihow.com/Identify-a-Sears-Kit-Home; Small Houses of the Twenties, 1926 house catalog reprint, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia /Dover Publications, 1991; Ken Harrison; Bernie Gray; and Bill Russell.)