Jim Bowman provided some treasured memories about his employment at King’s Department Store at S. Roan and E. Main in the late 1950s. Bowman further talked to three long-time employees of the firm: Louise Curtis; Ellen Sells whose husband, Sam Sells, owned the establishment; and Rose Cooper) to tap into their reminiscences. Another source of information was an interview of Mr. Sells conducted by former Press writer, Alice Torbett, just prior to the store closing in 1984.

Bowman commented on the painful days when the once thriving store closed: “When it became obvious that the time had come for King’s to close its doors permanently, Sam R. Sells postponed making the dreaded decision probably much longer than he should have. The employees were close-knit family members who regarded their job site as a second home. Many had been with the company the majority of their adult years.”

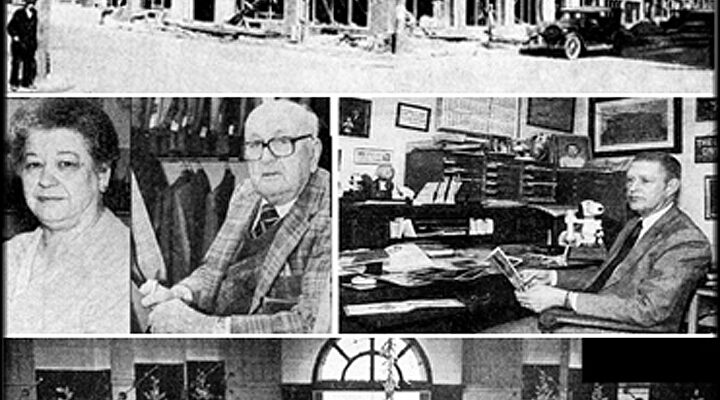

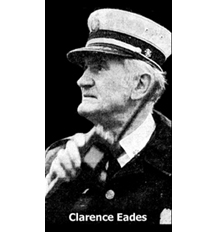

(L to R, T to B: King's Department Store under construction in 1928; Ruth Green and Ed Bateman, longtime store employees; Sam Sells at his desk just before he closed his business; and Main Street entrance during a busy Christmas holiday in the mid 1950s)

The former employee recalled a practice that King’s offered to its customers that is rarely, if ever, seen today: “Merchandise could be taken out on approval from the store and kept for three consecutive days, after which the item was either charged to the buyer or returned to the business. Some of those ‘approval customers’ pretended to own the home furnishings that they kept over the week-end – assumedly fooling” guests when having a party on Friday or Saturday night.”

Jim’s memories included the once popular pneumatic tube system that was popular in larger department stores of that era: “An interesting feature that intrigued young children was the method by which transactions were made following a sale. Although pneumatic tubes are commonplace now for drive through customers at bank windows, they were a novelty in the late 1950s. The clerk would place the sales slip and tended cash or check in a cylinder and place it in one of two tubes. It would then travel by vacuum in a pipe that ran above the store to a cashier who removed it, counted the money, put in the proper change and returned the missile in a second tube to the salesperson’s station.”

According to Ms. Torbett: “For most of the year, the fourth floor contained children’s clothes and some toys, but right after Thanksgiving a miraculous transformation took place when it became a fabulous Toyland with storybook dolls, electric trains, stuffed animals, games and mechanical toys assembled among fantasy castles and man-sized candy canes.” The floor became an intriguing setting for Santa Claus who, with his “luxuriant whiskers and resounding chuckle,” usually stood near the elevator and greeted youngsters as they sheepishly hid behind their parents.

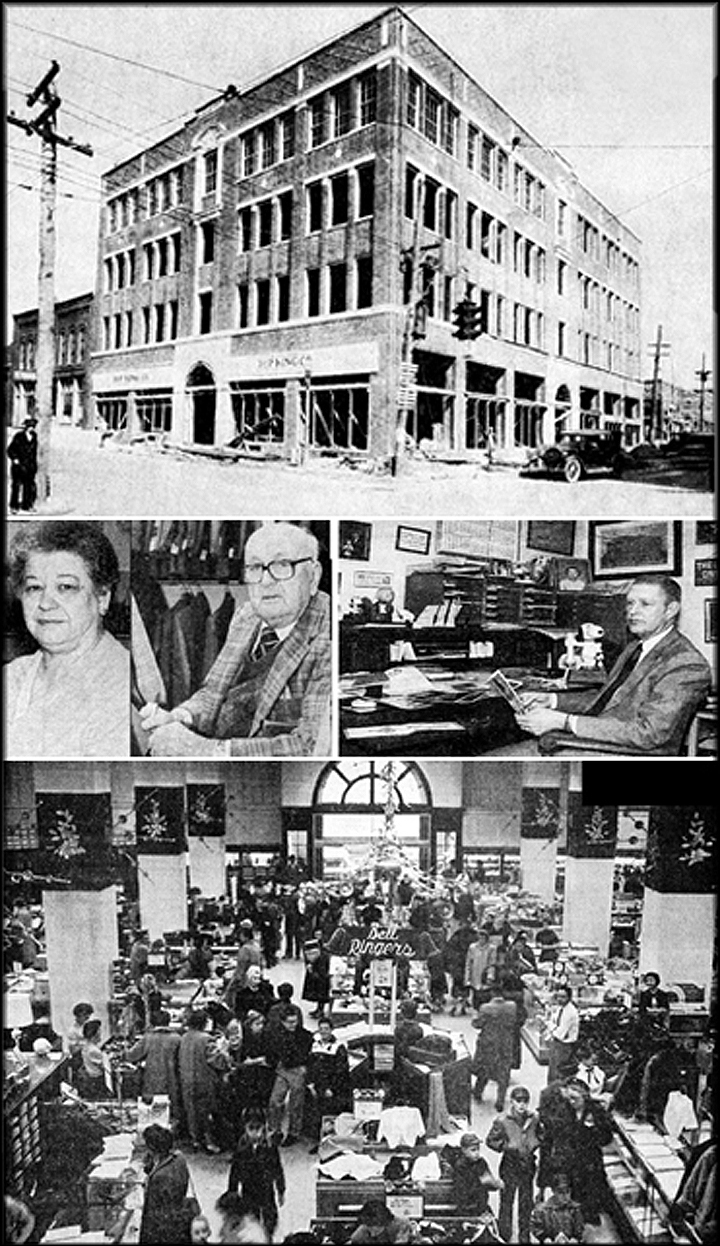

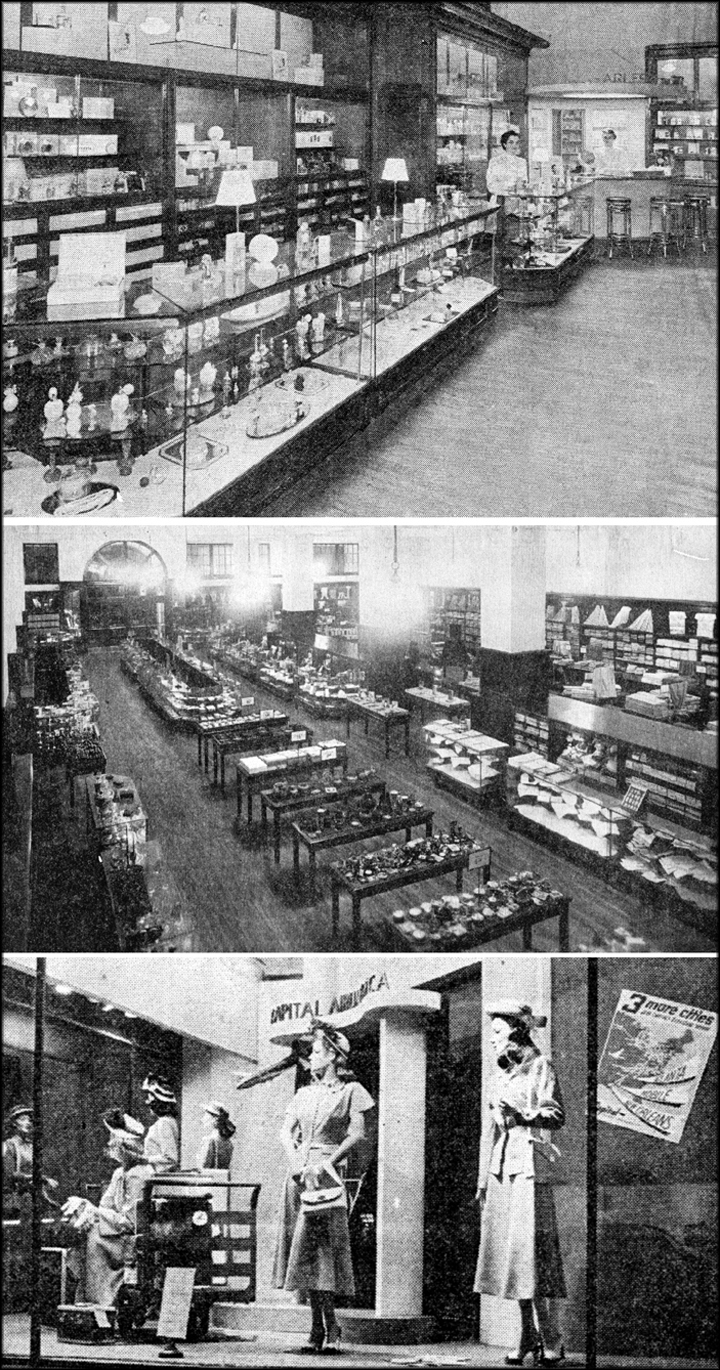

(L to R, T to B: Cosmetics Department located on the first floor; The store ready to open to customers on Monday, Sept. 24, 1928; and the popular display window at the corner of Main and Roan streets

Occasionally, people would head for one of the store’s large windows on an upper floor to watch a parade travel along Main Street. Others might go to the mezzanine and search for members of their family in the store below.

“To the delight of the close-knit sales associates,” said Jim, “two gatherings occurred annually to honor them. A storewide party was held in the administrative suite during the Christmas season and a picnic was scheduled each August at one of the city’s parks. Of necessity, the doors were closed for half a day each year for the latter event.

“King’s was always an extraordinarily clean place. When salespersons wanted cardboard boxes carried away, they communicated this desire to the night janitors by turning the empty containers upside down. Occasionally, a flood in the basement required a clean-up crew. The high water’s wrath brought on unexpected bargains on slightly damaged goods.”

Rose Cooper recalls when “several of us drove from Erwin to work at King's in the early 60s. I was in the book department with Stella Bowers. Customers bought and read Green Eggs and Ham as well as The Cat in the Hat long before the Dr. Seuss classics were popular in schools. The children were excited to get them.”

When this nonagenarian lady hand-knitted some items for the Sells’ children, their father was so impressed that he established a new department for her products. However, he opened it only after Mrs. Cooper promised to work in the downstairs (basement) store. Ellen Sells recalls a beautiful custodian, Minnie Gilley, who possessed a great personality that was conducive to salesmanship, being transferred to the china department.

Jim recalled that the nativity scene set up annually in the northwest corner window of East Main and South Roan was displayed years after the store had gone out of business.

King’s great five-floor department store was a pre-cursor to today’s shopping centers. Customers could locate almost everything they needed conveniently under one roof, park nearby and dialog with clerks who sincerely showed an interest in them.

Today, a drive east on Main Street or south on Roan Street always evokes fond memories by area residents who still warmheartedly remember King’s Department Store.