The Gump name stands tall in the annals of Johnson City history. A perusal of several old city directories yielded a myriad of Gump businesses over the years: A.S. Gump & Co. (Abraham S. Gump), Gumps (Martin I. Gump), Gump Brothers Clothing (Harry D. and Louis D. Gump), Gump’s Wholesale Grocery (Martin I. Gump), Gump Investment Company (Louis, Harry, Jay and Alan Gump), Bert Gump Insurance and Bert Gump Real Estate.

An area in north Johnson City, originally known as the H.D Gump Farm and later Hillrise Park subdivision, became what is today referred to as the Gump Addition. Mr. Harry Gump acquired the property consisting of 100 acres on Oct. 25, 1907 from Carnegie Realty Co. and Carnegie Development Co. The lengthy deed, written in typical land vernacular of that era stated:

“That boundary where the road, leading to and being near Holston Avenue and Baxter Street, crosses said branch; thence South 2 degrees 20’ West 494 feet to a set stone, … thence N 22 degrees 20’ W to a stake in the center of New Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues; thence with the center line of New Street in northerly direction to the center line of Sixth Avenue of said Addition; thence east with said center line of Sixth Avenue to the center line of High Street, …”

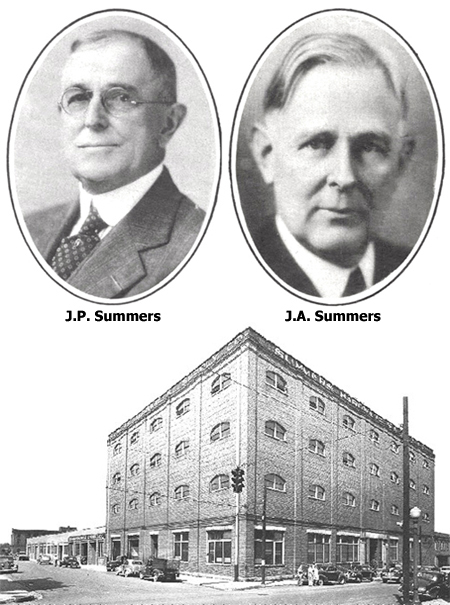

The Gump family is credited with another accomplishment – the naming of a number of streets in the Keystone community. The information came from the late Jay L. Gump, whose father and uncle bestowed the names to the streets.

In 1912, Harry D. and Louis D. Gump bought 132 acres in the designated area. They acquired the property from Mrs. Alice Earle who had obtained it from her father, A. Pardee Jr., builder of the narrow gauge railroad that brought iron ore from Cranberry, NC to the furnace in Johnson City.

A current map of Johnson City verifies some of the information found in my history archives. The land in question comprises 12 streets encompassed by East Main, Bert, Orleans and Broadway. Streets running parallel to E. Main are Pardee, Cranberry, Dyer, Colorado, Bettie and Orleans. Those running perpendicular to E. Main are Bert, Mary, Jay and Alan.

Harry and Louis, deciding to subdivide the land, named it Keystone because both men were born in Pennsylvania, the Keystone State. Then, with city engineer, W.O. Dyer, they began systematically laying out streets and assigning names for them. They decided to start by using the first names of their children in the order of their birth.

The first two named were Bert and Mary streets, the children of Harry Gump followed by Jay and Alan streets, the sons of Louis Gump. Having quickly exhausted the names of their children, the Gump brothers then picked other appellations that they deemed fitting. Pardee Street came from the name of the original owner of the property, while Cranberry Street represented the Cranberry mines and furnace.

Dyer Street was named after the city engineer. Colorado Street was chosen because the brothers and their family had moved to the Centennial State from Pennsylvania and grew up there. Harry and Louis had their first jobs in Colorado working in a men’s clothing store. One more street in the Keystone grid needed a name; this time the oldest grandchild, Bettie, the daughter of Bert was picked.

After the naming process was complete, the brothers divided the land into lots and sold them to individuals.

Today, the Gump Addition and the nine Keystone streets serve as reminders of a family who has lived and worked in Johnson City for over 125 years.