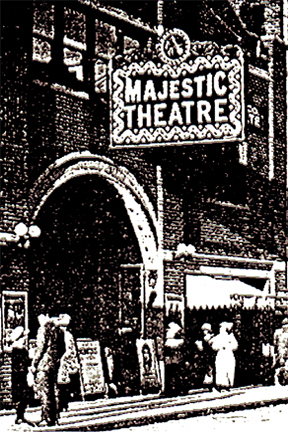

Most area folks can sadly recall Sept. 1, 1981 when the Majestic Theatre closed its doors forever. The beautifully designed edifice, built in 1902, served the city well for 79 years with first-run motion pictures.

Pre-1928 movies were a far cry from those of today; the first ones sported black and white images that could be seen but not heard. Silent features consisted of several six to eight-minute reels that were alternately played on two projectors. This monotonous labor-intensive routine required projectionists to work hastily so as to avoid annoying film interruptions. Advanced technology soon permitted movies to fit onto one or two large reels.

An organist or pianist, positioned in front of the flickering screen, was often used to provide musical accompaniment. Inscribed words on the big screen kept the audience knowledgably of the action. The Majestic’s owners purchased a “Mighty Wurlitzer” theatre organ in 1926 at a cost of $20,000. Frank Wilson was the first organist.

In 1928, major cinematic improvements occurred with the introduction of sound, the first offering being the 1927 “talkie” movie, “The Jazz Singer,” starring noted “Mammy” singer and actor, Al Jolson. Sound tracks were recorded on large record discs. To synchronize sight and sound, the projectionist carefully keyed the record groove with the “start” frame on the film. Miscues were normal fare with film breakage and record skips, throwing movies out of sync.

In those days, film advertising on theatre “fronts,” as they were called, was the responsibility of the owners, thereby requiring a staff artist to create new ones each time the movie changed.

The excitement of the first “talkie” motion picture to be shown at the Majestic Theatre can be sensed in a Sept. 13, 1928 Johnson City Chronicle article: “One of the most significant events in the history of motion pictures will occur next Monday, Sept. 17, when the Majestic Theatre introduces to the public of this section the marvels and wonders of this scientific age, Vitaphone and Movietone, pictures with a voice and soul.”

The article went on to state that Warner Brothers’ new technology was in its second year of existence and had been accepted at such leading cities as Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Atlanta, New York and Birmingham. The Majestic, affiliated with the Publix Theatres’ chain, was now ready to begin showing synchronized pictures.

The movie featured Al Jolson singing such songs as “Toot, Toot, Tootsie;” “Dirty Hands, Dirty Face;” Blue Skies;” and “Kol Nidre,” a Jewish prayer. Also included were the first talking news, Fox Movietone News, and other Vitaphone “shorts.” The Majestic Theatre owners expressed pride in being the first to announce the unique movie for East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia and Western North Carolina.

“The Jazz Singer” occupied the bill for the first part of the week and a new film, “Glorious Betsy,” played the second half. Matinee prices were 10 cents for children and 35 cents for adults. Showings after 6 p.m. were the same for children but 50 cents for adults.

The newspaper article concluded with a message from theatre management: “The Majestic Theatre extends an invitation to the people of the outside cities and towns to avail themselves of this opportunity of seeing and hearing the latest and best pictures at all times in Johnson City, as Vitaphone and Movietone will become permanent policy at this Publix playhouse.”